Years ago, one of the big New York slicks (I have no idea which one, though Esquire leaps to mind) ran a story purporting to represent the ranking of living American fiction writers. As I recall, it included a rather scary looking pyramid of scribbled names, topped by John Updike and Saul Bellow. There were no more than a few hundred names on the entire pyramid, all of which fit on a standard blackboard.

I've been thinking about that pyramid a lot over the past four days, during which the Association of Writers and Writing Programs' annual assembly (known as AWP) descended upon my snowy hometown of Boston, bringing with it more than 12,000 ink-stained wretches to mix and mingle and brood and kvetch.

Although it is many things to many people, the AWP conference is properly understood as the vast roving capital of American literary anxiety. Aspiring scribes come to get drunk and dream of fame. Dutiful mid-listers like myself come to dispense shopworn wisdom and feel famous, while legitimately famous writers—the ones at the top of the pyramid—come to meet the masses that adore their work and not coincidentally would like to be them someday. It's not the shape of the pyramid that's changed over the past few decades, but the plain fact that it now stretches down to the floor and out to the edges of the room.

If that sounds cynical, let me hasten to add that AWP is one of those manic, slightly regressive rituals (like college reunions or taking Ecstasy) that's easy to badmouth, but foolish to condemn. It amounts to a convention for lonely artists, aspiring and established, who mostly just want to feel less alone in their struggle.

Some background for the uninitiated. The Associated Writing Program was founded in 1967, by professors from a dozen creative writing programs. The idea back then was unity, creative writing programs being the red-headed stepchildren of English departments dedicated to squabbling over the merits of the canon, not updating it.

Creative writing has since become the academy's most unlikely growth sector. In 1975, the number of schools awarding such degrees stood at 79. As of 2010, that number was 852. And that's not counting the hundreds of writing conferences and centers that stretch from Key West to Fairbanks, Alaska.

The sheer scope of AWP is astonishing. The cigarette butts out front of the Hynes Convention Center alone had to number in the low millions. A human river packed the escalators, men and women of all ages and hues making their way to readings, receptions, and panels with earnest names such as "Don't Stop Believing: Leading the Writing Life After the MFA." The book fair filled two cavernous exhibit halls.

To the bemusement of the natives, the slushy streets of downtown were thronged with underdressed scribes swilling coffee and scribbling in Moleskin notebooks, downing cocktails at off-site parties, swapping gossip, engaging in public meltdowns and private hookups, many soon to be memorialized in prose or verse. Whatever else it might be, as a social phenomenon AWP marks the gathering of a large and largely nomadic tribe.

For first-timers, the experience can be daunting. On day two, I encountered an ambitious former student, a talented woman in her late thirties, who appeared on the brink of an emotional collapse. "I think I should have waited a few more years before I came to one of these," she said. "There are just so many … people." She meant, of course, so many other aspiring writers. When you're sitting at your keyboard, or in a small workshop, the notion that you're in competition with thousands of other hopefuls doesn't seem quite so in-your-face.

Even for writers with an enviable record of publication, AWP can be a dispiriting scene, a potent reminder of your place in the pecking order. The big names get the big rooms and the big crowds, as they should. But generally speaking, you're not forced to compete with them directly on the open market.

This awareness can be crushing to the wrong sort. At my first AWP event, a party thrown by a trio of literary magazines, I was buttonholed by a gentleman I'll call Glen, an author I'd met at a previous AWP. Back then, he'd cornered me in the hotel bar and proceeded to drop names for a difficult half hour. This time around he kept his rap to ten minutes, but it radiated the same unctuous perfume—of thwarted ambition curdled into desperate self-promotion. Sadder still, Glen seemed to be under the impression that I could somehow help his career. "Listen pal," I wanted to say, "if I could help your career, don't you think I'd be doing a better job with my own?"

There is, of course, this dark side to AWP. Writers find themselves using barfy marketing terms such as "networking" and "platform building." It's always off-putting when commerce gets its tenterhooks into art. In the case of literature—a niche product clinging to the margins of a frantic, visually dominated culture—it's close to laughable.

Then again, this is America, and the "aspiring writer market," as the comedian Bill Hicks might put it, is a hot one for manuscript consultants, publicity companies, and self-publishing outfits, all heartily represented amid the rows of literary magazines and poetry collectives. Another of my former students, a software developer, had arrived at AWP determined to bring print journals out of the dark analogue age, into the gleaming, miniaturized realm of digital devices, ideally at a healthy profit.

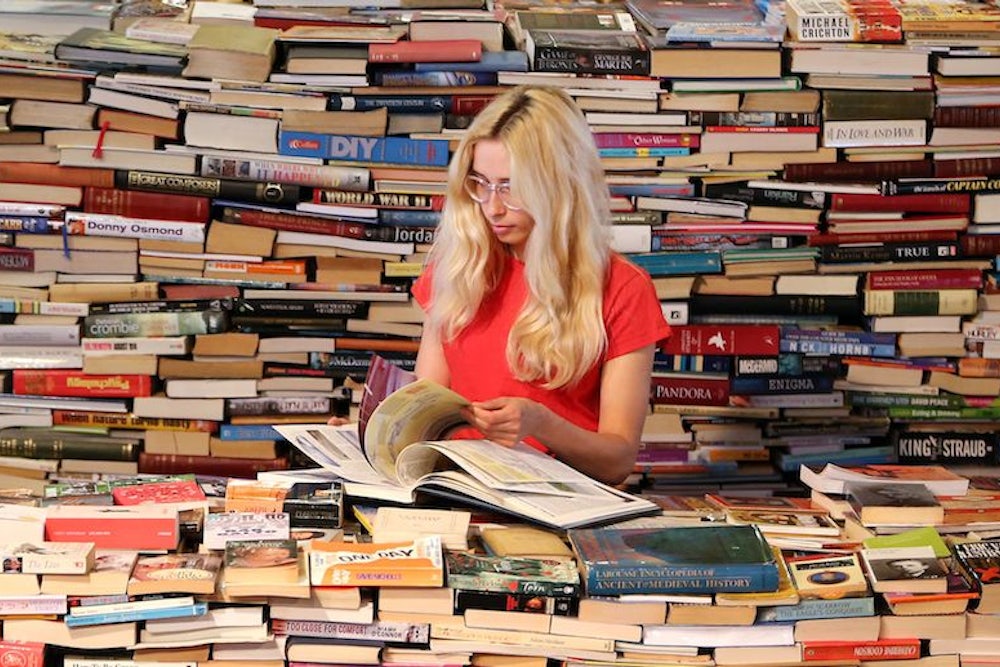

The happiest campers I met were the undergraduates and first-year MFAs, many of whom had spent years feeling like freaks for liking to read books and wanting to write them. They were thrilled to discover that they were part of such a large and voluble community. It was lovely to watch them scribbling down notes during panels. A lot of learning happens at AWP, though the central lesson (largely unspoken) is that there's no shortcut to putting in your hours at the keyboard.

One of my best friends, a well-regarded novelist and critic, tells me all the time that he loathes AWP. He feels it represents the degeneration of belle lettres into a professional class, with an adjunct industry that caters to wannabes who feel they have a story to tell, and thus expect to put a book in the world. I can't argue with him. (Or at least, I generally don't argue with him.)

But there's a larger and more unsettling truth lurking beneath his gripes, one that AWP inadvertently drives home: As a pursuit, literature is in a phase of incestuous contraction. Yes, people still read novels and stories and essays and poems. But today most of those people are also writers.

This was certainly true at the last event I did, a reading at a local bookstore. Every member of the audience, aside from a stray spouse or relative, was a writer. That's hardly an ideal model for increasing the population of readers.

Still, it was, like most AWP events, a sweet scene. One of the guys I met afterwards had flown in from Austin. Ray was about my age, mid forties, with a big tattoo on his left arm. He was a single dad with a couple of troubled teenagers. When he told me he had stories to tell, I didn't doubt it.

"How was your AWP?" I said.

"Amazing," he said. "There were all these people I'd only known online and it was so great to meet them, to become real friends. And there's just so much to absorb. I'm still buzzing." I have no idea if Ray's ever going to publish a book. I do know that he's engaged in a process of knowing himself better, and that his four days in Boston seemed to have helped him in that pursuit. Only a hater would begrudge him that.

Steve Almond is the author of seven books, most recently the story collection God Bless America.