Renoir is the film’s title, but it might as well be plural. It seems to promise a film about Jean Renoir just because it is a film, but it turns out to be about two Renoirs: Jean and his father Pierre-Auguste, the great Impressionist painter. It is also, to an equal share, about a young woman called Dédé who is seen in the very opening shot bicycling along a sunny road. This sequence is a tip of the hat to modern French film. Ever since Truffaut’s Jules and Jim, a girl-on-a-bicycle sequence has almost become a sign of membership in the club.

It is 1915, in the Riviera. Dédé is headed for the home of Renoir the painter, which is surrounded by lovely woods. She is taken into the old man’s presence. The people in the house, several serving women, call him “boss” affectionately, and we soon see why. This white-bearded man is direct and appealingly keen but also physically handicapped with severe arthritis. His very dependence on help makes him even more appealing. Dédé tells him that she has come to apply for work as a model, and he says, “Show me your hands.” This from a man who has painted dozens of nudes. He looks at her hands and says she will do: He likes the way light lays on them.

She becomes a model for him, clothed and nude, through the following days. One day while he is painting her as she lies in a reclining position, she asks if she may move. He tells her to move as much as she likes and goes on painting. Apparently he already has her figure in his mind. He becomes fond of her, though we never see any intimacy.

Then home from the army comes his young son Jean. In the cavalry in the war raging in the north, he was severely wounded in the leg and has been given sick leave. He and Dédé are soon attracted to each other, quite seriously—this young woman who is often being painted nude by his father. This is simply accepted as a fact by all.

Soon Jean and Dédé begin to discuss what he will do after the war, and she suggests the movies. (The actual details are slightly touched up here but are basically right.) He had been thinking of going into ceramics, where his father started, but she dissuades him. Anyway, a decision is postponed because Jean insists on returning to the army when his leave is finished—apparently it is his option—and he feels morally bound. He goes. Many of us know that after the war, Dédé became Jean’s leading lady in his first film, and also his first wife. (“Only when she had decided to become a film-actress did it occur to us that she should have a stage name,” he wrote years later. “We chose Catherine Hessling. I forget why.”)

As even the sketch above shows, there is no strong story, no climax. The film simply recounts some incidents in some lives. As it turned out long after, we are seeing a momentous decision when a man who later became one of the greatest film directors began to lean in that direction. But many of us knew most of it anyway. What beguiles us is the chance to be with these people at that time, by means of a picture that is so sympathetically acted and so pleasant to look at. Michel Bouquet as the painter, Christa Theret as Dédé, and Vincent Rottiers as Jean collaborate with the director Gilles Bourdos to give us the chance to revisit this fateful moment. And the fine cinematographer Mark Ping Bing Lee knows how to make it all look lovely.

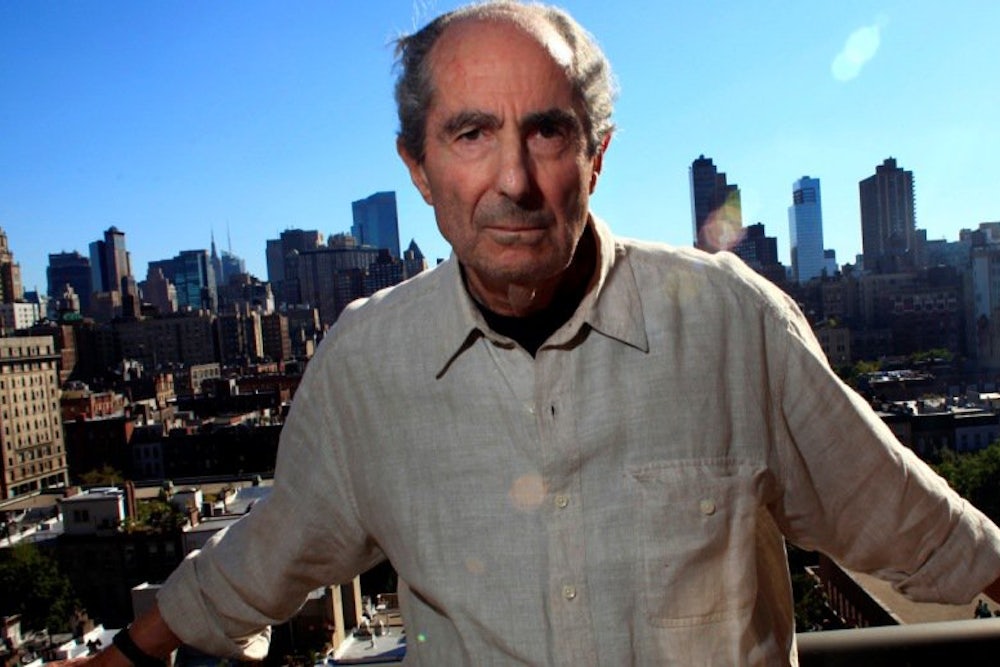

Philip Roth: Unmasked is a documentary made for television that is being shown in theaters. The first thing to note is that the directors, William Karel and Livia Manera, quite obviously won Roth’s confidence early. Almost eighty, he is relaxed, amiable, forthcoming. When it is his time to talk, he does so fully. No interviewer’s question is ever heard, he just talks. Of course questions may have been cut, but he seems to simply converse.

The second notable thing is the title. Roth has always seemed to me one of the most unmasked novelists of our time. His 31 books have always been essentially about Roth’s encounters with experience. He has never been a diarist or journalist, but he has made us feel that his novels were attempts to understand, explore, and portray what he has encountered in his personal life or as a citizen of our time. What he tells us here deepens some aspects of his life but is not often surprising. Moving around his country home and his Manhattan apartment, he recounts a summary of his career—how, for instance, he was called, with his first book, an anti-Semite because of his candor about Jews. In fact, the two outstanding themes in his career seem to be Jewishness as he has observed it and sex—his candor about which also has been assailed. What he must leave out is any account by himself of his writing, with its realistic crackle and its electric sweeps.

Personal note. His talk is interwoven with bits of interviews with friends, and here occurs an oddity for me. Jaunting around Europe from time to time in the past, I had noticed that bookshops usually carried translations of Roth’s novels, and I was glad of this interest in the thoughts and doings of a Newark Jew. Then I noted that Woody Allen’s films were also popular there—the thoughts and doings of a New York Jew. Now in this film about Roth, one of the interviewees is Mia Farrow, known for some years as Allen’s companion, who appeared in a dozen of his films. For me, an odd coincidence.

In any case, this film is an engaging look at a contemporary pilgrim and his progress.

Many, many pictures have been what we may call Setting Films. They began because of an interest not in the story but in the setting—a particular place or occupation. The result can be fine: Chaplin saw some photographs of the Alaska gold rush which inspired him to invent a story that took place there. A good deal of the time, however, the order of interest is plain. For instance, the recent film called A Late Quartet. Evidently a producer or director or both thought that a good picture could be made about the lives of the members of a string quartet. Then they got a screenwriter to invent a story that would exploit that setting.

Shanghai Calling is another instance. The producer or director or somebody discovered a reversal of the current problem of foreigners coming to the United States for work. A number of Americans—much fewer than the number of people who come here, but still a stream—are emigrating to China for work. They decided to make a film about this reversal and engaged a writer to come up with a story in that setting. In this case the setting is more interesting than the story, which still serves its purpose.

Sam Chow, a thoroughly Americanized young New York lawyer, is sent by his firm to its Shanghai office. He is not enthused: he thought he was going to be made a partner. But he has little choice. When he arrives, he is greeted in a businesslike way by Amanda, an employee in that office who has blonde hair and dark eyes and who speaks Chinese well. Sam does not. So we know from the start how the film is going to end. The cast, the script, and the setting keep up our interest, as does the setting. All of us have seen enough pictures of Shanghai to know that it is one more skyscraper-filled Asian city. But here we go into the buildings and apartments and restaurants and meet other Americans, mostly young, and it is all slightly amazing. The whole is like a colony, which is large and novel enough to be pleasantly disconcerting.

The story includes American veterans of China, and some essential misadventures for Sam. Eventually he makes a discovery that it is of great benefit to his company, and in one of his television conversations with his boss he is told that he has made good. This nicely fits his resolution of matters with dark-eyed Amanda. Daniel Henney is personable as Sam, and Eliza Coupe is even more so as Amanda. Daniel Hsia wrote and directed with agility, and he makes sure that his story doesn’t get in the way of his presentation of the city.