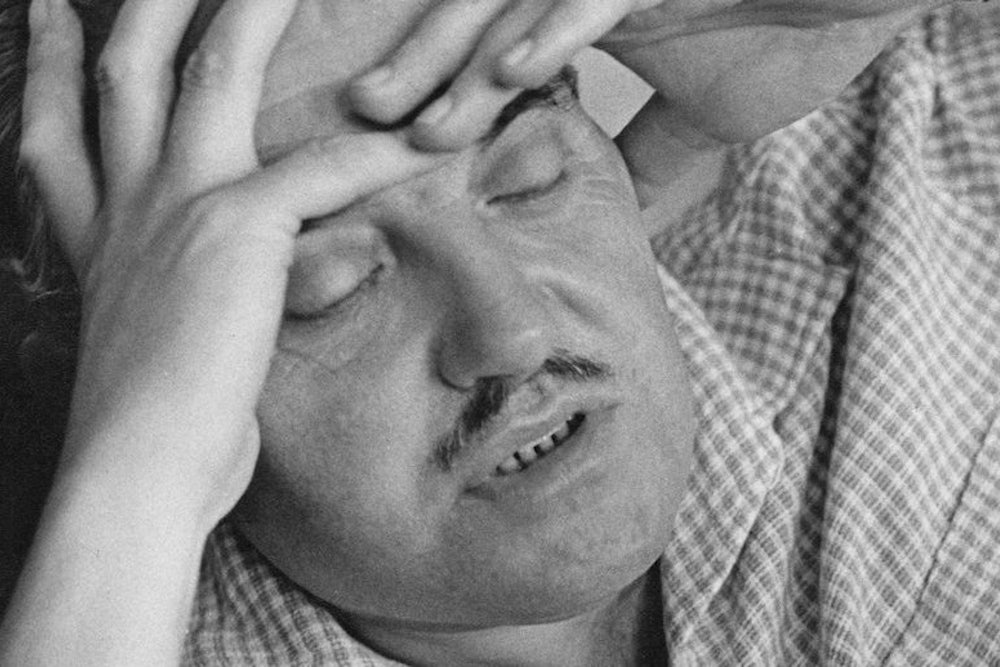

Are you as stressed out as I am? I only ask because, frankly, you look a little stressed. It must be the job. Or maybe the marriage. I mean, there’s so much to be stressed out about. Just look at the newspaper. Look at your bank account. Is your blood pressure rising yet? Well, you need yoga. No, wait, you need a drink. You need to relax. Because, with the way things are going, this stress is going to kill you.

That’s more or less the sort of bourgeois hysteria Dana Becker wants to flush out of our collective nervous system in One Nation Under Stress: The Trouble With Stress as an Idea. The book is a popular history of the especially au courant sort that will, I suspect, reach its apotheosis (or nadir) in a cultural history of the sneeze. As far as the genre goes, though, this is a fine entry, with Becker rather nimbly translating her obviously thorough academic research into readable prose. To her credit, she avoids both pandering to popular tastes and, on the other extreme, slipping into the professor’s phlegmatic tones. She does have the rather amusing tendency to pellet her sources with [sic]s, but that’s nothing to get worked up about.

Then again, Becker is plenty worked up throughout this book, and refreshingly so—intelligent anger is essentially extinct in today’s public sphere. Her primary objection is to our “elevating stress to the status of an actual disease,” which “has helped us avoid tackling larger social problems.” Not only are we all too ready to diagnose stress, Becker says, but then we revel in it, because it “mingles a certain pride in the fast pace of life with worry about its effects.” A similar argument proffered by Tim Kreider in an Op-Ed called “The ‘Busy’ Trap” made it one of The New York Times' ten most e-mailed articles of 2012. Both suggest that stress has become a status symbol, like an Ivy League sticker glaring from the back of a Volvo: I am important enough to have things to worry about.

Stress is a squishy concept, but just because it’s amorphous doesn’t mean it’s ahistorical. Far from it. Becker notes that Revolutionary War troops were thought to suffer from “Revolutiana.” While women trapped in what Becker calls their “gilded cages” had long suffered from the specious diagnosis of hysteria, it was the mid-nineteenth century neurologist George M. Beard who popularized the term “neurasthenia” to capture the budding anxieties of a rapidly growing nation. Becker brands neurasthenia a “particularly American disease,” since “the neurasthenic embodied both the upward trajectory of American life and the high price Americans were paying for rapid industrial growth and increasing materialism.” In other words, it was our ambition that caused our affliction, with the two becoming conflated in turn-of-the-century terms like “nervous bankruptcy.”

The idea of stress was further bolstered by the Mental Hygiene Movement of the Progressive Era, with its emphasis on cleaning out the dusty tenements of the mind. But it was not until Hans Selye published The Stress of Life in 1956 that stress became the meaningless catchall it remains today. A native of Hungary who came to the United States in 1931, Selye decided to treat the hardships of the Great Depression and World War II as psychological cataclysms, rather than purely social ones, thus setting into motion the machinery Becker rails against. A precursor of the self-help hucksters of our age, at one point, Selye cautions that “our reserve of adaptation energy is an inherited finite amount.” If you don’t know what adaptation energy is or how Selye measured its finitude, I am sorry to say that neither do I. Neither does anyone else, I suspect. Regardless, his idea stuck.

Becker is especially astute in pointing out how stress has been “gendered,” if I can dust off a verb from Intro to Lit Theory. Today’s stress, after all, is a not-so-distant cousin of the hysteria that was thought to afflict women; indeed, Becker is most deft in drawing out how society cruelly delights in praising women for how much they do while warning them in the same breath that they can’t do it all.1 Not that men get off easy. Reprising, to a degree, an argument made by Susan Faludi in Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, Becker says that modern society has deprived men of their traditional roles. The man in the gray flannel suit found himself both more aware and less capable of dealing with inward strife, so that Time magazine was lamenting by 1960 that “Many a young man rising fast in his profession is sinking fast physically.” The male version of stress, then, is the bundle of frustrations that comes with the nine-to-five cubicle grind—which, given today’s prudish mores, can’t even be alleviated by the imperfect-but-effective Don Draper triumvirate of Scotch, smoking, and strumpets.

But today, not only has the notion of being stressed-out come to embody a whole host of issues that may have non-mental underpinnings, but we are constantly told that we can marshal what the poet John Berryman smirkingly called our “inner resources” to wage an effective battle against this invisible enemy. This is Becker’s objection to the culture of stress: Stress exists, but it’s been blown out of proportion, falsely rendered, and has spawned an entire ecosystem of pseudo-psychological empowerment, from therapy to VitaminWater that purportedly offers relaxation.

Stress is not the issue, Becker says. Life is difficult, unknowable and often harrowing, and there is no use pretending that two minutes spent in downward dog is going to change all that. One more inclined to philosophy than sociology might note that we have replaced Kierkegaard’s prevailing anxiety about existence with a far more mundane unease, one we think we can eliminate precisely because it is earthbound.

The counterargument to all this is that our increasing awareness of stress reflects society’s increasing awareness of psychological ailments. It is, of course, comforting that the days of One Flew Over a Cuckoo’s Nest are long behind us and that one of our most popular television shows (“Homeland”) can deal with bipolar disorder with neither mawkishness nor condescension. But Becker deftly anticipates this counterattack, claiming that we have gone too far in medicalizing our lives: “The boundary between what belongs in the medical domain and what doesn’t has become more and more elastic.” She points to the DSM-V as chronicling every conceivable instance of distress, down to a broken fingernail. When absolutely everything is an ailment, then nothing truly is.

And Becker is especially adamant that the things we point to as the causes of stress actually stem from identifiable, concrete social or economic problems. She takes to task, for example, Andrew Solomon for writing in The New York Times Magazine that “poverty is depressing.” The issue for the poor is money, not serotonin; gay youth don’t need alleviation from stress, but tough penalties for bullies. She even applies this logic, carefully, to PTSD, making the point that war is hell, not stress. There are 175 ways to diagnose PTSD, and some 20,000 troops in Afghanistan and Iraq were on meds for “temporary stress injuries” and “stress illnesses” by 2008. These men and women may well need help, yet stress, in the end, winds up being a too-easy explanation of why we fight, who does the fighting for us, and how we make sure those fighters are integrated healthfully back into peacetime society.

Ultimately, I think that what Becker most fears is that the stress concept deadens us to experience—whether the experience of a soldier, a mother, or a spreadsheet jockey. Stress is a facile means of encapsulating everything about experience that’s objectionable, and then deaden it with pharmacological friends like Valium. As Becker asks at one point, “Is suffering normal or not?” The question is obviously rhetorical. Worse yet, I’m afraid the answer is not a particularly calming one.

Alexander Nazaryan is on the editorial board of the New York Daily News, where he edits the Page Views book blog. He is at work on his first novel. Follow @AlexNazaryan.

The Atlantic, for example, has become so notorious for its articles on the plight of la femme moderne that some jokester created a chart to describe the various pathways to loneliness, overwork and dread detailed in the pages of that magazine.