About 35 politically engaged people, almost entirely African-American women, sat in booths at Beggars Pizza on E. 147th, a long street lined with fast food outlets and boarded-up barbecue rib shacks in Harvey, one of the economically depressed suburbs ringing the Southeast Side of Chicago.

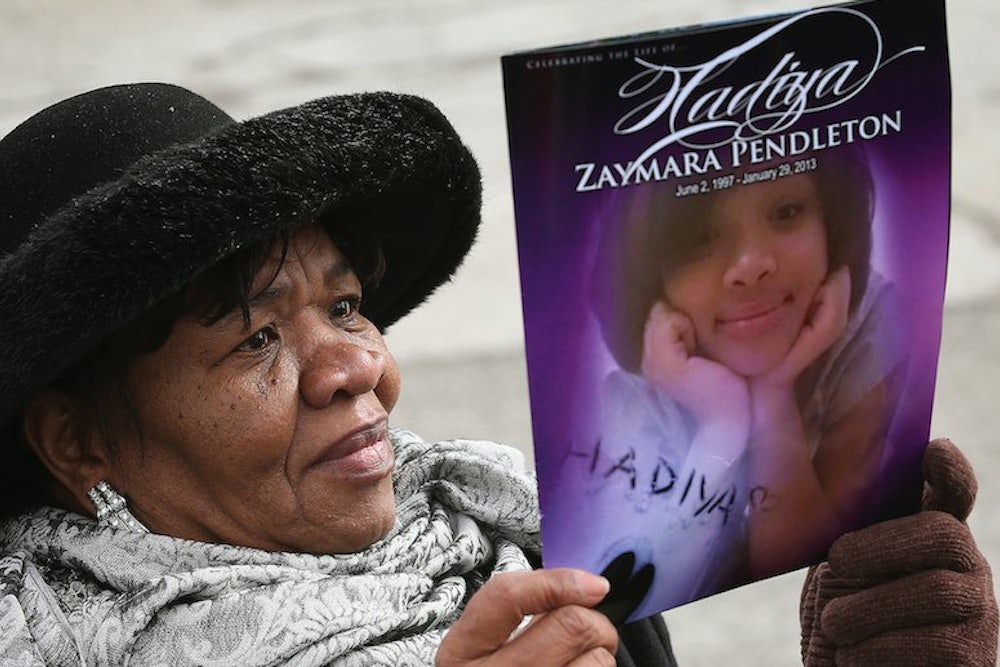

The women drank coffee or sipped water and ignored the doleful oration pouring from an enormous flat-screen TV: a live broadcast of the funeral service of Hadiya Pendleton, the girl shot dead in a Chicago park a week after singing in the presidential inauguration.

The funeral's inability to grab the room's attention was especially odd because we were at the pizza restaurant to hear from Robin Kelly, Cook County chief administrative officer and a former representative in the Illinois State Legislature. Kelly is one of sixteen candidates hoping to replace Jesse Jackson Jr., who had resigned his seat representing Illinois' 2nd congressional district in November after a bizarre five-month disappearing act, which culminated last week in a plea deal that could result in five years of prison time for diverting $750,000 in campaign funds to buy himself, among many other things, a $47,350 Rolex, $9,588 worth of children's furniture, and a $4,600 Michael Jackson fedora.

Kelly, whose first act in the Illinois House was to introduce gun control legislation, couldn't have asked for more compelling optics at a campaign stop than having Pendleton's funeral broadcast on the wall beside her. At a subsequent event, when I asked Alexi Giannoulias, a former Illinois state treasurer and close Obama associate, what the election is about, he leaned into me and said, "Guns, guns, guns." The Chicago Tribune wrote that Kelly is "almost single-focused on gun control." In a crowded field of largely unknown candidates, Kelly has surged in the polls by turning the special election—the Democratic primary is on February 26, and the April 19 general election is a mere formality in this blue district—into a referendum on Obama's firearms proposals. Michael Bloomberg's gun control super PAC Independence USA has upholstered Chicago airwaves with $2.1 million worth of ads lauding Kelly's lifetime F rating from the NRA, including $660,000 on a 12-day ad blitz in February. The advertisements have blasted Kelly's less pure anti-gun competitors, particularly a former one-term U.S. representative from the southern suburbs, Debbie Halvorson, who rejects an assault gun ban and in 2010 was voted out by an electorate that leaned GOP after redistricting.

The race to replace Jackson—who was the second straight congressman from the district to resign in disgrace—has been a magnet for Chicago's deep bench of unsavory elected officials who salivated at the rare open congressional seat. The circus began almost immediately in early December with the arrest at O'Hare Airport of a state senator, Donne Trotter, who had been one of the front-runners in the race, for allegedly trying to board an aircraft with a cache of guns and bullets. It took Trotter two weeks and more reports of ethically suspect behavior before actually withdrawing from the race. In recent days, two more candidates have dropped out and endorsed Kelly, notably Toi Hutchinson, a popular politician from the southern suburbs with an A- NRA rating who had been running a fairly strong campaign, trailing only Halvorson in polls conducted in January.

The other serious contenders still in the race are Anthony Beale, a Chicago alderman who threatens to pull urban voters away from Kelly, and Mel Reynolds, who represented the district in the 1990s until resigning his seat after convictions for statutory rape and soliciting child pornography. Reynolds has gotten little real traction in the polls however. "I think he's made genuine changes in his life, but you know, we can forgive him without voting for him," said Precious Luster, a politically active executive at Luster Products, a large hair product company in the 2nd district.

The district was redrawn in 2010 to combine mostly African-American neighborhoods on Chicago's Southside with a slightly lesser population of mostly white voters in outer-ring suburbs and in a few rural corners—the resulting boundaries were meant to retain minority representation for the district (in other words, a safe seat for Jackson). Before this became an election about guns, it was supposed to be about race. Halvorson, the former congresswoman, who is white and lost badly to Jackson in the last election, was positioned to capitalize on a balkanized black vote. Until recently, she was leading most polls with about 25 percent support. Her lead has dwindled, if not disappeared, as other candidates have withdrawn from the race—candidates that Halvorson believes have cut deals to ensure an African-American wins the seat.

The election was also supposed to be about the shift in competing centers of municipal political gravity, a sort of last gasp of traditional machine politics—an election no longer controlled by the Boss on the fourth floor of City Hall, but still largely determined by local powerbrokers. But then the local Democratic Party failed to settle on a candidate, Mayor Rahm Emannuel stayed out of it, and the Jackson family's tidal sway in this neck of Chicago politics—in November, Jesse Jr. won 65 percent of the vote despite vanishing entirely from the campaign trail—seemed to sink into the sand. "The redistricting means a different demographic, and so this election is not about who's got political power. It's a different kind of election, and so the result is it's become an election about issues, not an election imposed from on high," said Bobby Rush, the 11-term representative from the Southside.

Which is a new dynamic, more or less, for the 2nd district and Chicago as a whole. "Jesse Jr. has built quite an organization," Don Rose, a longtime Chicago political consultant who tends to back anti-establishment candidates, told me back when the special election had just begun. "What we may see, even though he's not running and is out of it, we may be still seeing Jackson's organization at work." When I spoke to Rose in December, he thought it likely the Jackson family would field a family member to run for the seat. "The Jackson family would like to have one of their offspring in there," he said. "Before the word was out that Sandi [Jesse Jackson Jr.'s wife, who was a member of Chicago's City Council] was under investigation it was widely believed she would jump in to replace Junior. Obviously that's no longer going to happen."

Newtown and the Pendleton killing galvanized the politics of guns just as the saliency of race and machine politics seemed to drain away from the election. But among Kelly's supporters at Beggars Pizza, I couldn't find anyone who prioritized gun control. Nina Graham, a retired high school teacher, told me that she had had it with all the gun messaging. "The gun issue is important—I don't want to say it isn't. But this needs to be about jobs, economics, and I'm going to tell Robin that." Graham made a beeline for Kelly when she arrived and returned to me a few moments later. "Robin told me not to make my point about guns. She's going to do it for me." And sure enough, Kelly began her speech by channeling Graham. "You all have gotten a lot of fliers about gun safety. But I'm keenly aware we have economic problems and underserved communities and we need to understand that no one wants to open a business here when they have to worry about getting hit by a stray bullet."

Most of the questions asked that afternoon in the pizza parlor were about the district's limited hospital services.

With so many candidates taking tiny slices of the vote, the margin of victory will likely be slim, and could be decided by white, liberal suburbanites who may not see gun control as a top priority—voters like Beverly Sokol and her husband Ed, both retired from running a women's clothing store, who live in an Olympia Fields subdivision of tidy one- and two-story homes just south of the big houses where executives from Standard Oil and Inland Steel used to raise their families. Olympia Fields has very few nice restaurants or upscale stores, and Sokol said the community lost a professional golf tournament when the mayor asked the PGA to help pay for the event's police detail. "We don't have any hotels in Olympia Fields so it's not like we got any revenue from it anyway," said Beverly, a small white woman in her 70s. Still, Olympia Fields is a world away from Ford City and the other desperately poor Chicago neighborhoods of the 2nd district burdened with rampant teen pregnancy and epidemic gun murder rates.

Thirteen years ago, Jesse Jackson Jr. asked Beverly to include Jackson's wife Sandi in one her regular community brunches, called "The Delicate Balance," that she hosts in honor of successful women business leaders. Jackson wanted Sandi to be introduced around the suburban part of his district. "She was new to the area and didn't know anyone," Sokol told me. "I was happy to do it."

Soon, the Sokols were Jackson supporters. "He understood what the area needed and he was very independent, and we voted for him, a lot of us did," she said. Her neighbors, said Beverly, are the descendants of white flight but have moved on from Chicago's tradition of racial identity politics. "There are a lot of people in these south suburbs who live here now because their parents moved them out of Chicago in the dead of night. But since then, these are people who also have been able to cross over invisible lines. It's not the black and white divide."

As Beverly talked, she carried trays of desserts to the table, where Ed and I sat and listened. First came cookies and cakes, then coffee and plates of sandpaper-rough chocolates, then, incongruously, a heaping bowl of hummus and torn pita. "Jesse has been painful to watch—they were so dynamic both, Jesse and Sandi. It's pathetic. Disappointing." Beverly continues: "In the last few years something changed and the result has been this area has really been suffering from neglect." Sokol pushed cookies toward Ed. He pawed one and added, "Obviously we need a new ethical standard that we've lost." Beverly, who said she knows most of the candidates personally but supports Kelly, told me whoever wins the election will need to focus on the poorest parts of the district most urgently.

I met Debby Halvorson, a former Illinois State Senate majority leader, for a greasy breakfast at Ted's Restaurant, a thriving diner in Calumet City, not far from where Al Capone once kept a house. She told me she had visited 49 black churches in the district. "African-Americans own guns, too. Trying to make this about guns instead of jobs misunderstands what this district is concerned with," she said. Halvorson touted the time she shared in the state Senate with Barack Obama, and that she supported 90 percent of his legislative agenda when she served alongside him in Congress.

Halvorson wants to close gun show loopholes and make background checks universal, and told me she can act as a broker between the NRA and gun control advocates in Congress. But when Halvorson's husband, who had joined us at Ted's, said 20-round ammunition clips might be excessive, she cut him off. Chicago has tallied some 40 gun-related killings since the beginning of the year, 12 gun murders in the first six days of January alone, and Chicago's heavy-hitter politicians, like congressmen Danny K. Davis and Jan Schakowsky, have begun to line up behind Kelly. "I want another member in the Black Caucus, yes," Davis said to me at a Kelly campaign event announcing his endorsement (alongside a slew of other Chicago politicians, including Trotter, the candidate who withdrew after being arrested for carrying guns on a plane). "I also want another member of the Progressive Caucus."

Whether guns can be a successful wedge issue in this election is widely viewed as a harbinger for the 2014 midterms, and Kelly's campaign manager told me that his polling shows 65 percent of district voters would not consider a candidate with an A rating from the NRA. No polls in the race show Kelly commanding anything close to that kind of lead, although Kelly's campaign has released internal polling indicating she has climbed to a four point lead over Halvorson, up from a distant third in polling conducted in mid-January.

At the pizza parlor, one of the few men in the room stood up to ask Kelly whether she had supported closing a local medical facility. Kelly replied that she supported the facility's plan for "reengineering" its services to save money and better focus its care on pressing community needs. "We can't force private hospitals to provide emergency services, and it's clear we have a real need for them," she says. "Which brings us back to guns."

Ilan Greenberg has written for The New York Times Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Wall Street Journal, and Slate, and teaches writing on international affairs at Bard College.