2:05 p.m. EST, 3:05 a.m. in Beijing: 5:55 to air

Mike Walter—white, above-average height, bestowed with the news anchor’s kind face, gentle voice, good hair—cannot find his Chinese teacher. He’s wandering the halls, checking in conference rooms and offices, and occasionally stopping coworkers to impress them with his favorite phrase in Mandarin, one which has little relevance to everyday life and is singularly unhelpful in trying to locate his class, but which has become his signature saying nonetheless, in the unreasoned way some things in foreign languages just feel natural to say, and others do not: “You are not Chinese.”

Which is almost always incorrect, because Walter works in the Washington, D.C., broadcast center of year-old CCTV America—a bureau of China Central Television’s English-language channel, CCTV News—where just about everyone is an employee of the People’s Republic of China, including Walter and his classmates. Walter is one of three anchors who platoon as hosts on CCTV America’s main program, “Biz Asia America,” which earlier this month expanded its programming from one hour a day to two (plus a 30-minute current events and debate show Walter hosts on the weekend). You may have never heard of him, or his program, or even CCTV News—which has been around, in one form or another, since 2000—but according to Jim Laurie, a former TV correspondent and senior consultant for the channel, Walter is accessible to a billion-plus people in China, some 40 million Americans, and as many as 100 million people in other parts of the world. CCTV News doesn’t use Nielson ratings, so it’s hard to know how many actual viewers it has. But it’s conceivable that Walter, though mostly unrecognized on D.C. streets, is watched by more people than CNN’s Wolf Blitzer or even Fox’s Bill O’Reilly.

Unlike his cable-news counterparts in America, though, Walter draws his salary from the Chinese government. You may wonder whether that makes him a Communist mouthpiece. It does not. CCTV News isn’t the propagandist machine that other China’s other state outlets are, and Walter is, by all appearances, a typical American journalist. He studiously reads the corrections pages of the Washington Post and drives his writers crazy demanding they confirm every fact, has the habit of sprinkling “allegedly” and “reportedly” around his anchor copy when they fail to do so. Last month, I overheard a conversation between writers in the newsroom. “One of the founders of insurance giant AIG is suing the US Government,” one of them read from the script. “Taxpayers had bailed the company out…” Back and forth they went, trying different wording, working the copy until they felt it read well, but repeatedly missing a detail that to Walter was fundamental. “It’s not the founder!” he said, exasperated. The man suing the U.S. government, Maurice “Hank” Greenberg, was the company’s CEO, but hadn’t even been born when the company was founded (in China, of all places, in 1919). Walter’s correction didn’t make it onto the Teleprompter during the broadcast, so he adlibbed it live on air.

Indeed, it was Walter’s ability to work “off-prompter,” and his journalistic rigor, that appealed to the CCTV bosses when they set up shop in D.C. toward the end of 2011, says Laurie. The channel’s other hires included veteran producers, correspondents, and anchors from “60 Minutes,” Bloomberg News, CNN, CNN International, BBC World News, ABC News—all in the hopes of producing global news with an Asian focus, rather than bare cheerleading for the People’s Republic. For the most part, they’ve succeeded. Sure, recent coverage of an electronics-related trade dispute was perhaps overly critical of China’s Asian rivals, and its coverage of Obama’s second inauguration was heavy on cute young Asians along the parade route, but that’s about as suspicious as CCTV News gets. If you’re looking for a channel that’s religiously critical of America, you’re better off watching Russia Today, which two years ago underwent an expansion similar to CCTV News’.

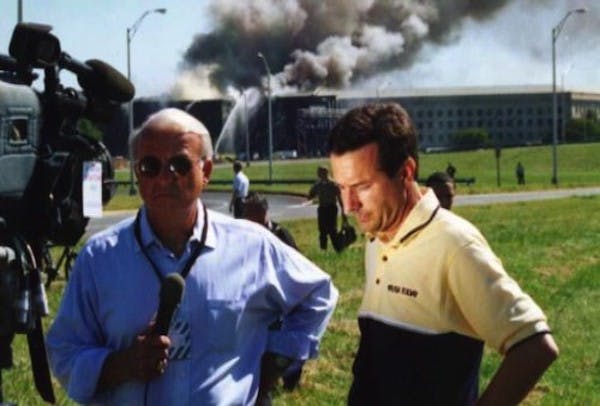

Walter, as the saying goes, is as American as they come: the home in the suburbs (of Northern Virginia), the pretty family (one daughter, one son), even the midlife career reevaluation after 9/11. After years as an anchor in Tampa, he was hired by WUSA in Rosslyn, Virginia, which is where he was headed one day when he heard on the radio thatplanes had hit the World Trade Center. Stuck in traffic, he beat on the steering wheel, knowing that he’d be sent to New York if only he could get to the office. Then he heard a jet engine and looked up to see the underbelly of a Boeing 757, and watched it bank, dive, and crash into the Pentagon.

“I was a local anchor chasing the big stories, all about my career, but 9/11 really impacted me,” he said. “I think I looked inward more than I ever had.” Though he kept anchoring he began work on a documentary about journalists who cover traumatic events, and kept looking for opportunities to engage more meaningfully with the world. It was the People’s Republic of China that gave him one.

“The best way for me to describe it is, just from a personal standpoint, I would anchor two hours of news on local TV, and by the end of the show, I’d feel I lost a percentage of my IQ, talking about Paris Hilton and Britney Spears,” Walter said. “Now when I get off the air here, I feel I’ve learned something about the world.”

6:05 p.m. EST, 7:05 a.m. in Beijing: 1:55 to air

Mike Walter is waiting patiently behind the anchor’s desk. Before tonight’s live broadcast, he’s recording a pilot for the new two-hour version of the show. In the control room, an energetic directoradministers profanity to his colleagues, while in the studio, a few boom-mounted cameras pirouette around the room showing Walter from a half-dozen different angles, and another camera on a robotic dolly chugs slowly across the floor with no apparent direction, like a curious alien, at one point coming so close to Walter that his face blows up in the control room monitors and allows a pore-level view of that mask of makeup rarely seen outside TV studios and open-casket funerals. The wrong image was on the monitor next to the anchor desk; then the right image was up but wasn’t a good image; then Walter’s co-host tripped over some lines; then there were typos on the Teleprompters. Producers and assistants sprinted in and out of the control room to put out little fires, spraying a little more profanity around as they went. It was, in short, a little bit of controlled chaos, a team stumbling around a bit, finding its legs.

But excitement, too: The atmosphere here is “like a start-up,” a few employees said. The Chinese bosses of CCTV have made the folks here feel that their work really does matter, and that what they’re doing is remarkable in part because of who they are, because the employees come from all over— Chinese executives and American consultants, South Africans in front of the camera and Filipinos behind it, Chinese journalists who’ve worked in America and American journalists who’ve worked in China. They feel like the A-team that China HQ has called in to raise the quality of its reporting everywhere, the hope being that D.C. serves as a model for CCTV’s other broadcast centers—that the polish of a Mike Walter might rub off on the anchors in CCTV’s other two broadcast centers, in Beijing and Nairobi.

It’s a remarkable thing, when you consider that CCTV is owned by a country Reporters Without Borders calls “the world’s biggest prison for journalists, bloggers and cyber-dissidents.” In the U.S., China is doing what few American news organizations are—hiring journalists—while at home, it’s putting its own to forced labor.

This is the precisely the kind of image problem China is trying to address—or obscure?—with CCTV News. Late to the soft-power game, Beijing has always struggled with public relations, and the channel is intended to “present some alternative views that may not be heard in the mainstream media,” Laurie explains. Take the Renminbi, for example, a perennial point of contention, with the Chinese constantly accused of manipulating their currency for an unfair trade advantage. “Whenever you watched Fox News or even CNBC, you would get the take that Chinese are purposefully not allowing the currency to float or fluctuate.” There was rarely rebuttal, so thought the Chinese, and if no one else would carry the Chinese view, the Chinese would do it themselves. They started the English language channel in 2000, made it look and feel as similar to respected international news outlets like the BBC World Service as they could, and then, last year, began broadcasting not just to, but from, Africa and America. The idea was to be “close to regions in which they wanted to make an impact, set themselves up there as more than just a news bureau, originate programs from this area, brand it, and market it.” A Chinese perspective is more convincing to Americans if it’s coming from America (or to Africans if its coming from Africa).

The danger, given the Chinese government’s penchant for propaganda and hostility toward journalists at home, is that if CCTV News were to lose its relative editorial independence —if a communist party boss were ever to call a producer and demand that the channel criticize the Japanese over a skirmish in the East China sea, or ignore some Chinese offensive action—the viewer might not notice the difference, at least not right away. It would still look and feel like real news, striving for real balance, with Mike Walter, a real journalist still delivering it.

James Fallows, national correspondent for The Atlantic, who has lived in and written books about China—and has appeared several times on CCTV while there—finds this worst-case scenario unlikely. “I’m in the ‘not very alarmed’ camp about its expansion,” he said in an email. What’s more, “they do some coverage of the U.S. and the non-China rest of the world that is a useful adjunct to what people would see on CNN, MSNBC, and so on.” When CCTV News first started broadcasting out of D.C. a year ago, Fallows “was struck that when they were covering U.S. or European news, they did a pretty good job, and they had the same traits that you associate with good non-U.S. perspective, a broader perspective.” He qualified his praise, though: “When they were covering news out of Beijing, that was familiar CCTV coverage.” CCTV News may be covering the world well, but perhaps it’d be naïve to expect a media company run by the Chinese government to be critical of its boss.

And yet, even that might be changing. I was milling about the CCTV America newsroom last month when a half dozen monitors set to different stations all flicked to footage out of Beijing. CNN, MSNBC, BBC—they were all showing the Chinese capital. In fact, they were all showing the same building: none other than CCTV’s Beijing headquarters, that giant Escherian wrenched-square where the CCTV bosses work, peeking out from behind a nearly-opaque layer of smog. Beijing’s air pollution had hit a record high that day, and while I waited for a flushed executive to burst into the newsroom and fumble for the TV remotes, or for awkward glances among the staff, or for a stern phone call from Beijing with instructions on how to handle the story, none of that happened. It didn’t happen in CCTV’s D.C. bureau, and apparently didn’t happen in Beijing, either: the Global Times, an English-language version of a Communist Party tabloid, even published an editorial demanding that the government “publish truthful environmental data to the public.” “Two or three years ago,” Fallows says, “the state media would say, ‘Oh we have fog.’ And now they say, ‘This is terrible and we have to do something about it.’”

Does this mean CCTV bosses are finally willing to show the world some of China’s warts? Or did they simply realize they couldn’t hide a story that citizens, merely by looking up into the sky, could see for themselves?

8:00 p.m. EST, 9:00 a.m. in Beijing: On air

Whatever the reason, and whatever change is or is not happening in China’s treatment of the press at home and abroad, the important thing for Mike Walter is this: Tonight on “Biz Asia America,” reporting live from D.C., he gets to cover air pollution in Beijing.