Last Monday night, February 4, when talk-show host Stephen Colbert demanded that his guest, Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, reveal her "most conservative belief," Justice Sotomayor shot back, "I believe in the Constitution." Colbert parried, "Then I believe you're not a Democrat."

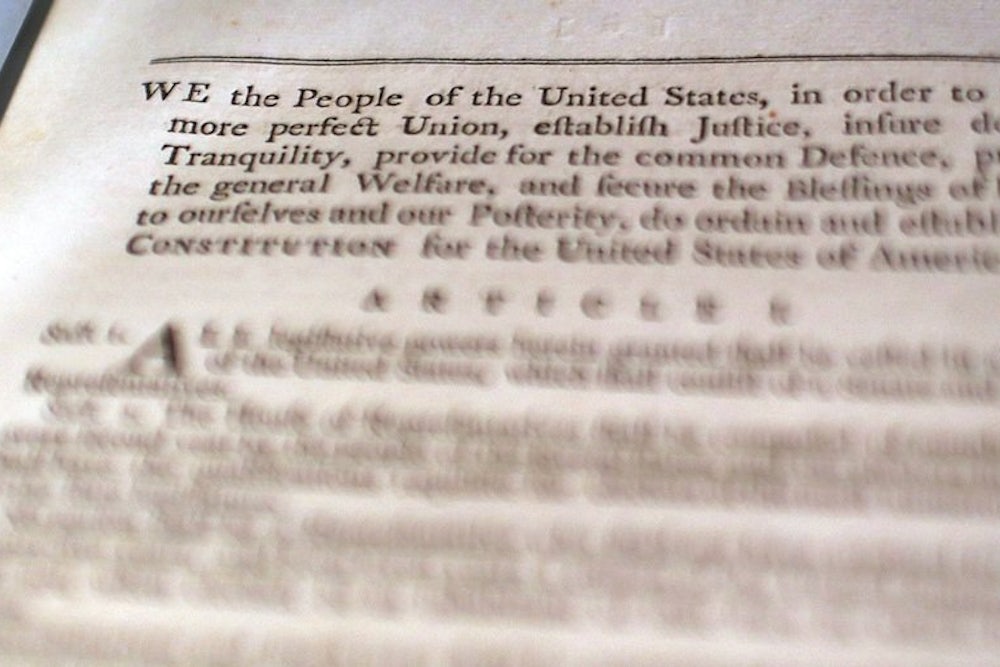

Laughs all around. But, in reality, the laugh is on Democrats and progressives. For decades, they have shied away from embracing the Constitution or showing why it supports their goals. Meanwhile, Republicans and conservatives never miss an opportunity to wrap their agenda in the founding documents and their framers. For example, in last October's first presidential debate, when moderator Jim Lehrer asked the two candidates for their respective philosophies of government, President Barack Obama stumbled through his answer without once mentioning the Constitution. In contrast, Mitt Romney deftly pointed to the backdrop behind the stage, a blow-up photograph of the original handwritten text of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and said, "The role of government is to promote and protect the principles of those documents."

The time may be at hand when progressives change their habitual tone-deafness to constitutional argumentation. If so, the change agent will be Obama himself. Since his re-election, the president has not only pushed an unabashedly progressive policy agenda. Less noted, but more novel, he has grounded his political case for that aggressive agenda in the "enduring strength of the Constitution" and the ideals of its framers. Largely ignored on the left, Obama's out-of-the-box tack has provoked ire on the right. Last week, the Republicans' top Senate Judiciary Committee member, Senator Charles Grassley of Iowa, delivered a lengthy riposte to the constitutional brief Obama included in his January 16 opening pitch for strengthened gun regulation. "The president's remarks," Grassley complained, "turned the Constitution on its head." Similarly miffed, Paul Ryan scolded Obama for "invoking the Constitution and Declaration" in his inaugural address, "sort of as a means to legitimize his very partisan, very ideological agenda."

In his inaugural, Obama's evident first goal was to knock down the claim endlessly reiterated by Ryan and his allies, that the 1789 Constitution mandated "small government," incompatible with twentieth and twenty-first century progressive reforms. "The patriots of 1776," he gibed, "did not fight to replace the tyranny of a king with the privileges of a few." Hence, their vision, and the words they drafted to enact it, are hospitable to laws passed by subsequent generations, as they have "discovered that a free market only thrives when there are rules to ensure competition and fair play." In addition to this populist thrust, the president offered a second originalist rationale for activist government. Government power, he argued, is often necessary to give real-life meaning to the individual rights prescribed by the Declaration and the Constitution: "While these truths may be self-evident, they've never been self-executing . . . . [P]reserving our individual freedoms ultimately requires collective action."

Obama deployed this rights-based defense of affirmative government to support enhanced firearms regulation, in unveiling his gun control initiative. While acknowledging the Second Amendment, he cited other constitutional guarantees—free exercise of religion, peaceful assembly, and life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—as rights also to be weighed in calibrating the government's responsibility to curb the threat and reality of gun violence. Indeed, it is this specific claim that provoked Senator Grassley's push-back. "The Constitution," Grassley insisted, "limits only the actions of government, not individuals," adding that the "President reads the Constitution differently than it has ever been understood."

As it happens, it is Grassley's account of constitutional history that is wrong. While Obama's reading may push the envelope of current constitutional doctrine, it echoes that of the Reconstruction Congresses which enacted the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. In line with then-existing Supreme Court precedent, they believed Congress empowered to prevent private interference with the exercise of individual rights created by constitutional prohibitions on government. Specifically, they held the federal government responsible for preventing private violence and intimidation designed to deter former slaves from voting and enjoying other constitutionally prescribed liberties. And they wrote into the amendments express authority for Congress to "enforce" that responsibility.

Thus, in addition to yoking contemporary progressive goals to the vision of the Revolutionary War generation, Obama's emergent constitutional canon appears bent on revitalizing a cornerstone of the Civil War era's—more unequivocally progressive—vision. Indeed, he seems already to have sparked an incipient dialogue around that prospect.

By engaging the right on the meaning of the Constitution, Obama has broken new ground. For progressives, he has sketched a fresh template for countering their adversaries' long-unanswered constitutional narrative.

Simon Lazarus is senior counsel to the Constitutional Accountability Center, a public interest law firm, think tank, and action center.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the date on Monday. It was February 4.