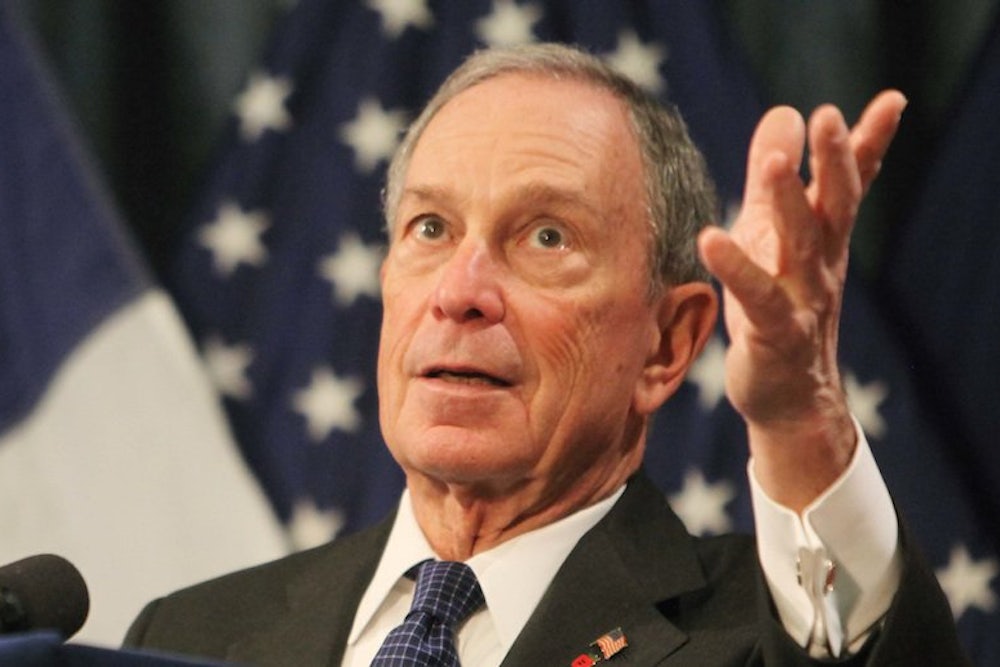

Michael Bloomberg has been accused, during his long tenure as New York’s top executive, of seeking to play many roles other than the one to which he was elected. When he pushed aside the previous term-limit stipulations, “King” was bandied about most often. (It also comes to mind when you take a gander at his "baronial" decorating style.) Another favorite, thanks to his bans of cigarettes and soft drinks (and his hoped-for one of Styrofoam), is “Nanny.”

But if we’re going to caricature Bloomberg with a job title inside the frame of reference of the average kindergartener—and after eleven years of the same guy at the same job, this is the kind of article the press is forced to write—the correct one to use these days is Fairy Godmother. It’s a role Bloomberg has settled into as he’s realized the limitations of democracy: As he prepares to give up dreams of a crown, increasingly, what he has sought to do—and what we the public have come to hope for from him—is to wave a wand (or a wallet) and magically change everything into something fancier, safer, better. New York City, rounding the corner into the final years of Bloomberg’s last term, is filled with new sparkling castles and well-heeled Europeans who like to dance in large gaudy rooms—just like something out of Grimm’s or Perrault (or Disney, as anti-gentrification critics love to point out). And, as is seldom noted about but equally true of his fairy tale counterparts, Bloomberg isn’t especially interested in consulting the beneficiaries of his largesse about what their vision of a better life might be

Most recently, the mayor has set his charitable sights on gun control, as anyone who watched the Super Bowl would have seen in this ad he funded. But Bloomberg has always been a philanthropic guy. Even before he made his fortune, friends remember him sending checks to the NAACP, just as his very middle class father had. He gave on a grand scale once he’d become uber-wealthy, setting up the Bloomberg Philanthropies Foundation. Once he became the wealthiest elected official in United States history (even fairy godmothers treat themselves to something special every once in a while) he broadened his reach, giving to more city-based charities. Bloomberg told critics that he wasn’t trying to gain political allies with his expanded giving; rather, he came into contact with more worthy causes thanks to the requirements of the job.

Whatever you might think of his more run-of-the-mill plutocratic instincts, it’s worth considering Bloomberg’s approach to the city’s budget. Elected as a Republican, at least in name, the new mayor not only raised property taxes (part of what’s helped all those glittering castles go up, and which has transformed who can afford to own in the city), but he also took a scythe to the bottom line of a city facing a deficit of $6 billion by initially cutting across all agencies except police and fire—but made up for it by giving private gifts to many of the arts organizations whose budgets he’d cut. His deputy Patti Harris told New York’s Chris Smith that “He doesn’t mix up private philanthropy with the city’s budget.” And yet the mayor’s office dramatically expanded a public-private partnership that allowed him to even more directly shape what kind of social programs New York has invested in. One of his largest gifts to the fund has been for a program meant to help young minority men get a step ahead, a worthy cause that also, conveniently, might assuage anyone inclined to criticize his administration’s unprecedented stop-and-frisk program as racial profiling of those same young minority men.

In recent years, as Bloomberg’s national profile has gotten even higher and he’s turned his sights on what his next step will be, the mayor has turned his fairy godmothering to a number of causes that happen to be near and dear to liberals’ hearts. He recently showered his alma mater, Johns Hopkins, with a gift of $350 million, much of which is earmarked for needy students and the rest of which will go towards the school’s research in fields like water conservation When the Susan G. Komen Foundation last year very publicly pulled its Planned Parenthood funding, Bloomberg wrote a big check, to round applause from progressives. And now, in the wake of Newtown, he has very publicly renewed his anti-NRA lobbying, releasing an ad, and is pledging that his newly formed SuperPAC will back anti-NRA candidates. (“You can organize people, and I can write checks,’ the mayor explained.) The left is so delighted at the discovery of its own fairy godmother, so attuned to its wishes, that it seems largely happy to ignore the fact that private funding as a substitute for more lasting government programs more or less goes against its first principles—not to mention all that liberal hatred for Citizen’s United. It also appears happy to ignore the inherent unfairness of fairy godmother patronage, which by its very nature is idiosyncratically selective: For instance, Bloomberg—whose candidacy was overwhelmingly supported by well-off New Yorkers but not their lower-income citymates—found Occupy Wall Street, with its calls for systemic (if inchoate) overhauling of the financial system, distasteful. And so poof, with a wave of a wand and a permit, Zucotti Park was cleared.

One thing Bloomberg’s PAC probably won’t back, according to reports, is a candidate for New York City mayor in this year’s election, unless it seems as if his legacy is under an existential threat. He’s supposedly tried to get someone who shares his high profile to seek the job; it’s clear Bloomberg has come to believe that the everyday politicking that was a requirement of the job for many years is less effective than celebrity or money, which allowed him to escape the timewasting pretense of average joe-ness most politicians must pursue, leaving him free instead to do thinks like ostentatiously fly his personal helicopter. In the meantime, Christine Quinn, his supposed heir apparent, was quoted in a recent New York profile saying that the mayor hates seeing her in flat shoes: perhaps he’d like to see his Cinderella in a bit more of a glass slipper look?

But whoever ascends next to the mayoralty, whatever his or her net worth, will have to deal with Bloomberg’s budget legacy: while he was busy reshaping the city and now the country, the mayor also continued to hew to his fiscal-prudence principles. Much like congressional Republicans, he’s sought to impose spending limits without increasing taxes any more. The result has been that the city faces deep cuts to both education, and a bitter dispute over contracts with the teacher’s union that might mean losing a huge chunk of state funding. “The next mayor’s going to have some very, very serious problems—very,” Carol Kellermann, president of the Citizens Budget Commission, told the Times. “That is a very serious problem looming, and nobody seems to have an answer for it.” It’s a useful reminder: As attractive as they might seem in an era when traditional legislative means of governing sometimes seem to have ground to a halt, even fairy godmothers have their limits. It’s almost midnight, and the coach turns back into a pumpkin. For Bloomberg, too: soon, without a city government to wrestle into submission, he’ll just be another free-spending liberal, cutting checks like it’s going out of style.