Back in December, when Paul McCartney united with the surviving members of Nirvana to play a song at the 12-12-12 Concert For Sandy Relief, people could be forgiven for thinking of the performance as an attention-grabbing one-off. After all, multi-performer good-cause concerts are less well-known for high musical standards than for unlikely artist pairings. (Usually involving Bono.) But for rock listeners who came of age in the 1980s and 1990s, the spectacle of the ultimate Generation X group jamming with a Beatle had a certain unplanned resonance, one that spoke to much more than a communal interest in coming together to help hurricane victims: The alternative rock they grew up listening to had become the new classic rock.1

In fact, yesteryear’s alt-rockers have been on a Remember When2 kick for several years now. And its components hew pretty closely to the trail blazed by the aging dinosaurs they used to mock. There have been reunion tours (Soundgarden, the Breeders), fawning documentaries (Cameron Crowe’s Pearl Jam Twenty), nostalgic media retrospectives (“Turn 20” remembrances on the influential music blog Stereogum commemorating the anniversaries of albums like Alice in Chains’ Dirt), and rereleases whose price points are distinctly more appealing to middle-aged consumers than youthful indie fans (a lavish box set from Rage Against the Machine, a multidisc version of Nirvana’s seminal Nevermind album).

On the face of it, there's nothing wrong with any of this.3 Plenty of people are happy to pay good money to hear "Loretta's Scars" live during Pavement’s reunion show or check out a demo version of "Porcelina Of The Vast Oceans" on the lavishly art-directed reissue of Smashing Pumpkins’ entire oeuvre. Why shouldn’t middle-aged artists be free to monetize songs they wrote in their twenties? Veterans of scenes from rockabilly to psychedelia did the same thing—and they did it well before mp3s and Spotify came along to pole-axe everyone’s back-catalog royalties and make finding new revenue a practical imperative.

All the same, the intellectual lineage of alternative rock means devotees might feel a particular discomfort watching their heroes go down this road. Rock fandom has always featured a heady component of generational warfare. But fans of alt-rock—or at least the critics and intellectuals among them—had a generational critique that went well beyond don’t-trust-anyone-over-thirty tribalism. The basic gripe was against a corporate music structure that kept innovative acts out of the spotlight while guaranteeing recording contracts and radio exposure for aging Baby Boom bands like The Who (or people doing an extremely poor imitation of them). This was, of course, an exaggerated complaint, but a very real one at the time.4 Alternative rock wasn’t just a different sound. It initially represented an alternative channel for getting fresh voices in front of audiences.

Eventually, and probably inevitably, the movement broke wide, and started getting exposure (and money) the old-fashioned way—something that caused no shortage of agita among fans who debated whether this represented selling out.5 And these days, it can feel like Pearl Jam and their peers did the taking-over-the-establishment thing a little too well. The summer music festival circuit, once an indie staple, is larded with '90s retreads. On the few alternative rock stations that still exist, you hear a lot less from deserving young artists like Chairlift or Japandroids than from vintage alt bands like Nirvana (or a people doing an extremely poor imitation of them). In fact, there’s plenty of nineties music alongside the seventies and eighties stuff on classic rock stations.6 No wonder: We are only a few years away from seeing the Clinton era’s flannel clad rebels inducted in to the the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. (I don't have the heart to make the Miley Cyrus inducts Nirvana joke.) Meet The New Boss. Sounds kind of like the Old Boss but with more feedback and angstier lyrics.

Is there anything wrong with this? Sure, no one wants to feel like a geezer, which is exactly how you feel if you’re uncomfortable with the idea that the Nevermind baby is now old enough to drink.7 But alt-rock’s generational argument was always felt more intensely by intellectuals than musicians, whose taste in music tends to be much more catholic. Sure, everyone hated The Eagles, Styx and various other easy targets. But Kurt Cobain, Eddie Vedder, Billy Corgan and their peers loved The Beatles, David Bowie and Black Sabbath. A lot of them even liked ABBA and The Carpenters, punk guilt be damned. Listen to the music—instead of thinking over the mode of production—and you find that alternative rock was basically a combination of punk energy, art rock conceptualism and classic rock hooks, the exact ratios changing based on the aesthetics of the artist. They didn't want to rid the world of Led Zeppelins; they just wanted a non-derivative Led Zeppelin of their own. This is fine, of course, because Led Zeppelin and The Beatles got their start doing their own spin on their heroes. It's how art works.

Critical canonization often does more harm as good. For listeners, music is a living, breathing thing. It needs to live inside of us. We need to figure out our own relationship with artists and songs and what works for us and what doesn't. If the cultural shockwave subsides, the art's ability to touch your heart and quicken your pulse remains. A well thought out reissue or a reunion tour might help someone reassess a group they hadn't thought about in years or put something worthwhile on the radar of an open-minded, younger fan.8 Reunion tours and boxed sets are just vessels—and decreasingly relevant ones, too. The tired cliché that really demands an alternative is rock music’s9 endless fascination with generational debates that can never be resolved.10

When I was young, The Beatles first truly came on my radar during the media push for The Beatles Anthology. (What can I say? My parents mainly listened to NPR.) I felt a great pressure "to get it" that was both very palpable and utterly absurd. I felt like I had done something wrong by not understanding the world changing greatness. It wasn't until I realized a few years later I needed to start listening For A Great Band With Songs I Might Like And Possibly Love instead of The Band That Changed Everything that things clicked for me. Time eventually makes all art seem less revolutionary. When I was young the idea that Elvis was considered shocking seemed ridiculous, as I am sure that young people today don't understand why Snoop Dogg or The Sex Pistols used to terrify people. One day it will please us to remember how upset people got over Odd Future and Skrillex.

The Boomers tended to crow about How Great It All Was that it became hard to listen, but younger fans aren't going to have the same problem. Fans of newer acts have followed the lead of alt-rockers when it comes to embracing a new delivery system that gets them out from under the bootheels of the oldsters in the entertainment conglomerate’s corner office: Do you think people who grow up listening to Spotify or Kickasstorrents.com care one whit about box sets and radio airplay?11 The digital-download bonanza-slash-complete collapse of the music industry that started in the Aughts turned out to be a much more substantial change to the music industry than anything that came out of Seattle, and it helped insure that aging Generation Xers won't have the same hegemony to completely dominate the conversation. This is for the best. But those same aging Generation Xers will still continue to get nostalgic about their favorite music, but fortunately in a much more humble fashion. This too is for the best. After all, someone has to tell the kids that Sleater-Kinney will change their life.

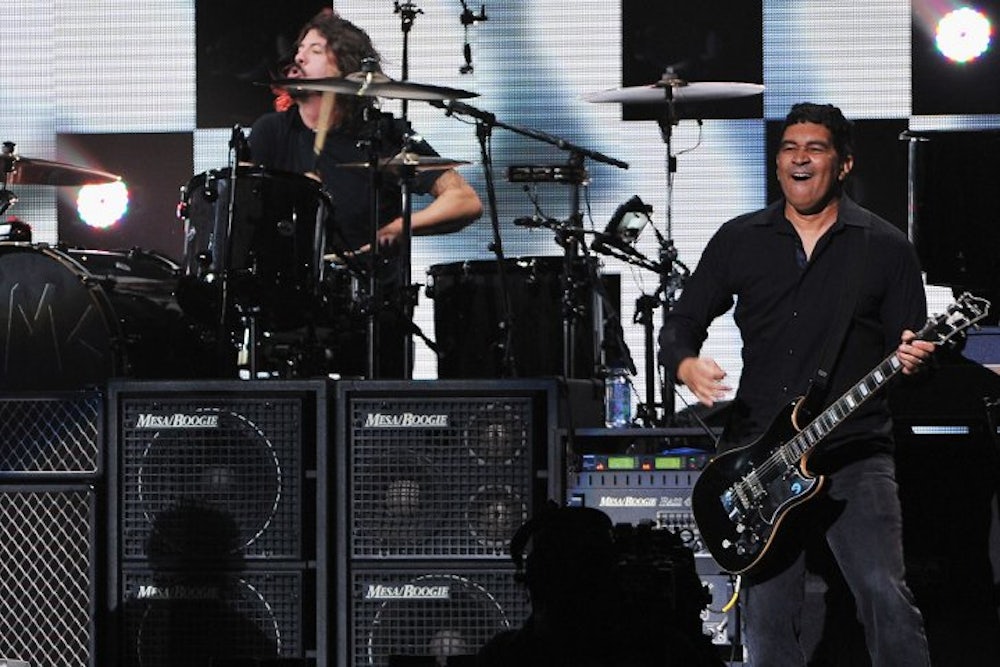

"Cut Me Some Slack," the new song that McCartney, Dave Grohl, Krist Novoselic and Pat Smear performed together, was originally written for Grohl's upcoming documentary Sound City. It's a pretty solid fuzz stomp, and a nice reminder that McCartney is at his best when his innate choir boy aura has a gritty counterbalance. Hopefully you didn't go in to this hoping for "In Bloom" times "I Want To Hold Your Hand."

Tony Soprano cannot be pleased about this.

I will straight-up have a nervous breakdown if Blur do not tour America this year.

Consult a back issue of Spy, a Douglas Coupland novel or theBoomer Santa song from Community for more elucidation on this idea.

Read any zine or back issue of The Baffler for more elucidation on this idea.

"Even Flow" is the new "Feel Like Making Love." I promise you that I am not going out of my way to make you feel old.

Time is a goon.

Did you hear those Sugar reissues from last year? More bands should try to rip off the guitars on "Gift."

Very generally speaking, being stuck in the past is a much greater problem for rock radio stations than pop and hip-hop radio stations. Lunch-time retro hours aside, these stations are relentlessly forward moving, which is overall a good thing. Pop and hip-hop should constantly feel new and exciting. If rock station programmers had a similar hunger, we wouldn't have to keep dealing with the Rock Is Dead meme every few years. That said, the all-new-everything drive is probably a bitch if you're George Michael and you want to tour arenas.

The debate about which generation did it better is a debate for another time, though most people tend to think the music they were listening to when they first started driving, falling in love and smoking pot will forever be the best music that ever existed and there's little point in trying to change their mind. Should your adolescence happen to sync up with a musical movement later considered respectable, consider yourself lucky.

Well, maybe a little. While the internet has made it easier for artists to find fans, very few acts manage to become huge without crossing over from internet sensation to mainstream airplay.