My grandmother slept with the poultry man to help feed her six children, my mother told me many times. "We had nothing," she used to say, "but a piano." Over the past month, I've been living with Beck Hansen's Song Reader, a collection of 20 original songs that Beck released in the form of sheet music, the primary delivery system for popular music a century ago, and I've been picturing my aunts and uncles as kids, gathered around that piano in their house, warbling old songs very much in the spirit of Beck's new ones, at night after a big chicken dinner. Owning a piano was once more than the symbol of middle-class aspiration that it became for my grandparents; it was a virtual necessity, one of the only ways to have music in the house in the days before radio and records came into widespread use. Popular songs had to be designed for playing and singing, rather than listening, and the hits among them—like "After the Ball," by Charles K. Harris, which sold more than five million copies of sheet music—had broadly acceptable sentiments expressed in catchy words and music simple enough for ungifted amateurs like my mother to perform.1

Far from gifted as a pianist or singer myself, I've plodded and crooned my way through all twenty of the songs in Beck Hansen's Song Reader, on my own and with a couple of friends, and I've listened to or watched dozens of the performances of the songs posted on the project's website since McSweeney's made the collection of songs available for purchase in December. This is a piece of work that takes some doing to know well, because doing is exactly what it takes. The project is no doubt off-putting to some people who cannot read music at all, not even as slowly and tentatively as I can, and that may well be fine with Beck. It certainly doesn't hurt his image as an exceptionalist to provide a sizable portion of his audience with a work that is, by conception, out of their reach. The sphere of art-pop that Beck occupies is a clubby one, and the most elite clubs have always attracted members by exclusion.

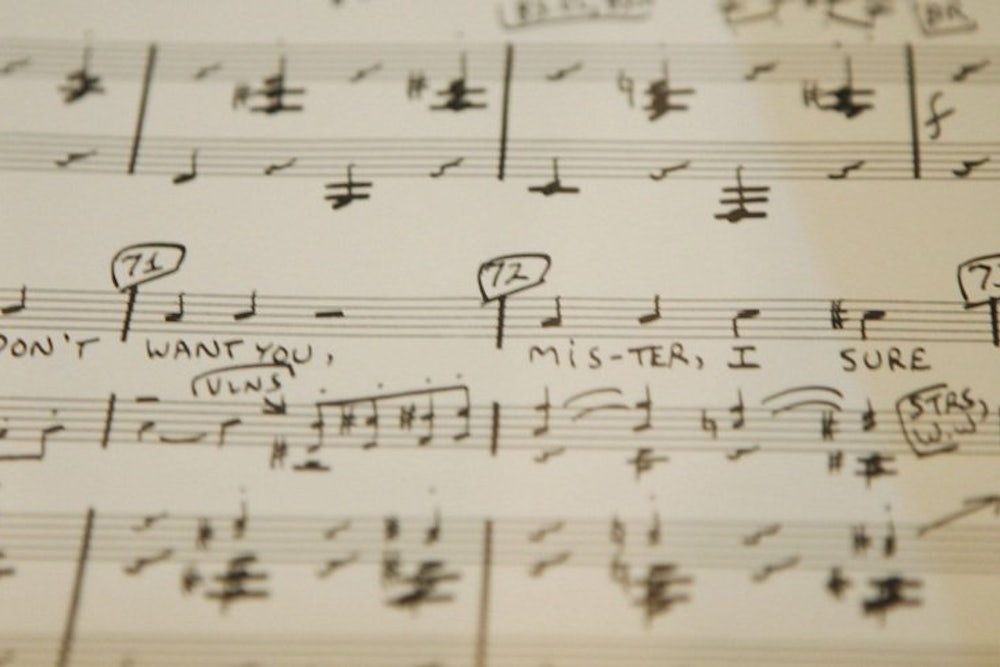

Like many great songs of the sheet-music era, most of the tunes in the Song Reader are simple and conventional, though a couple are unexpectedly tricky. The collection's most conspicuously dark piece, "We All Wear Cloaks," is composed in 7/4 time (with an odd bar in the chorus in 3/4), and there's an elegant ballad called "Heaven's Ladder" that changes keys twice.2 Melodically, all the songs are conversationally tuneful, designed for singers with narrow ranges. Then again, so are all of Beck's songs, because Beck has a fairly narrow range himself. No harm. Tunefulness isn't measurable by the number of notes, and Beck is a good (if not great) melodist.

The Song Reader is a gimmick about gimmickry—terrifically clever and exquisitely well executed, but still a gimmick. In spirit, most of the songs Beck wrote for the project draw heavily from the pool of comically juvenile novelties that dominated the landscape of primordial Tin Pan Alley. In fact, three of the most deliciously odd song titles in the Reader, "Rough on Rats," "The Wolf Is on the Hill" and "Leave Your Razors at the Door," were titles of actual songs in the late nineteenth century. (In the Reader, Beck's "Leave Your Razors at the Door" appears as a song excerpt in a mock advertisement on one of the song sheets.) The ditties Beck concocted with the old titles are not much better than the originals. Though they're more contemporary in musical feeling and more overtly poetic, they're essentially jokes. Like a great deal of the material in this songbook, they wear their novelty for cover, as a rationale for providing little more than a few moments of amusement.

In his past work, the lyrics have been the great strength of Beck's songs, and the words of the tunes on the Song Reader are the project's weakness. The writing may be his most disciplined, his tightest; but, overall, it doesn't have the kinetic free-association fire of his usual work. In "Just Noise," a lightish swing tune, the lyrics read, "If you hear my heart breaking/and you don't know what it is/don't be alarmed/it won't do you no harm/It's just noise." And in "Last Night You Were a Dream," the lyrics go, "Last night you were a dream/now you're just you/and I am just a fool/someone you once knew." One hears, in this writing, the sound of an artist trying too hard to be someone or something else, a writer stifled by the limits of homage—the tyranny of emulation. The tunes on the Song Reader are finely made and genuinely enjoyable to play and sing, as well as to listen to in "user" performances. Still, Beck is not Irving Berlin, and there's no point in his trying to be. I'd much prefer to have Beck back.

The name of Charles K. Harris, the one-time "King of the Tear Jerker," appears on more than 300 songs, though Harris was always suspected of having purchased tunes from writers who went uncredited or acknowledged only as arrangers. As the early-twentierth-century musicologist Signumd Spaeth wrote in his lofty-minded History of Popular Music in America, "The career of Charles K. Harris remains a convincing proof that one can become an enormously popular songwriter without ever writing a really good song."

In 7/4, a signature in septuple time, each bar of music has seven notes of roughly equal duration, instead of the typical three or four notes—making the music sound overpacked with notes. Examples in pop music: "Money" by Pink Floyd and the verses to "Ethiopia" by the Red Hot Chili Peppers.