The coin of the realm in today’s techno-visual culture is the GIF, a file that supports brief animations repeating endlessly. GIFs had a moment of particular resonance last summer, when extraordinary displays of athleticism from the Olympics were converted from full video into short loops, recurring endlessly, devoid of meaning aside from the aesthetic. Then came the presidential election, with its loops of the candidates at their most ill-at-ease; and after the Academy Awards, reaction shots of every unsuccessful nominee will probably appear. For its power to reveal through repetition, the GIF has became a medium unto itself. The Oxford English Dictionary named “GIF” the 2012 word of the year.

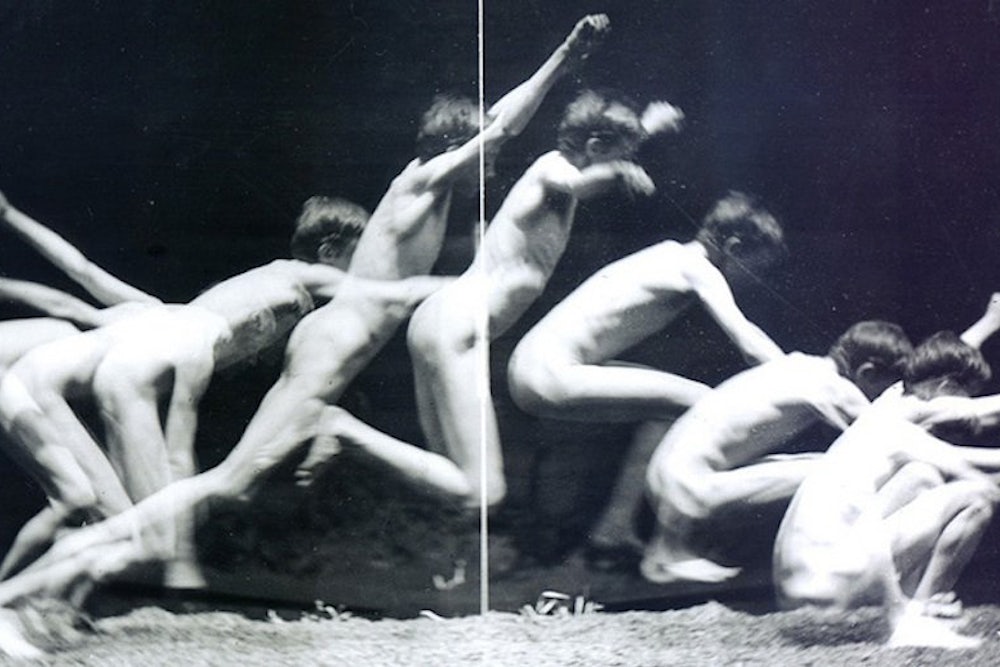

This is the legacy of Edward Muybridge, an English-born, late nineteenth-century photography pioneer famous for his study of a horse in motion. You’ve probably seen it at some point: a jerky film of the animal running. Muybridge devised the image to help settle the question of whether the four feet of a horse ever rise off the ground at the same time while trotting. (They do.) He went on to document all manner of motion, ending his career with often openly sexual nudes. Trotting horses and black-and-white bodies may seem far from the varied nature of contemporary photography and film. But moving images stripped of narrative context—a medium Muybridge mastered more than a century ago—are the visual currency of the moment. Muybridge broke down motion in order to help his contemporaries understand it; today we break down motion to understand a little more about the ephemeral details of life.

In divergent ways, three writers have recently sought to bring the spiky, peculiar, and accomplished Muybridge into the present day. Two are non-fiction, Muybridge: The Eye in Motion by Stephen Barber and The Inventor and the Tycoon by Edward Ball; and one is fiction, Moments Captured by Robert J. Seidman. Barber makes the most explicit case for Muybridge’s contemporary relevance. “Within the immediate demands of digital culture,” Barber writes, “memory is not subject to gradual habituation and attachment ... it becomes transplanted directly into the dynamics of corporeal movements, such as those Muybridge envisioned in the 1870s and 80s.”

But Ball and Seidman attempt to make Muybridge seem newly relevant as well. Ball describes Muybridge’s story, and his relationship with his patron Leland Stanford, in the novelistic historical approach—akin to true-crime novels such as The Devil in the White City—while Seidman sees in Muybridge’s life the outlines of a contemporary romance novel, and isn’t afraid to fictionalize brazenly to make it work. Barber’s book may be the only one that will satisfy Muybridge obsessives. Ball and Seidman, however, cast their own light, if not upon the man, then upon the degree to which legends are made even of the least likely—and least likable—figures.

No one of the three new books provides anything like a definitive understanding of the man, and it is quite a story: Muybridge emigrated to the United States and then travelled around the country. A former bookseller, he learned photography while recuperating back home in England from a stagecoach accident. He later claimed the head trauma had caused a loss of sanity, when on trial for killing his wife’s lover. (He had found letters between the pair.) After the murder, his wife died and Muybridge abandoned his son Florado, concentrating on photography with what came to be diminishing returns. By the end of his life, the studious Muybridge had been outshined by more showy impresarios. He retreated into more animal photography, and then into retirement, having chosen to advertise his photography at the World’s Fair in a theater he named “Zoopraxographical Hall,” alienating audiences accustomed to flash, not science

While Barber’s book presumes a great deal of familiarity with Muybridge, focusing on the semiotic meaning of a scrapbook the photographer kept throughout his life, Ball’s The Inventor and the Tycoon presumes nothing. Ball’s book explains every one of Muybridge’s name changes (he began life as Edward Muggeridge and ended it as Eadweard Muybridge) and goes into some detail about his image-making. He also describes the process by which, for instance, Muybridge produced a panorama of San Francisco—dragging a cumbersome camera through the city streets over the course of hours, and binding the photos together with an unbroken sheet of linen.

But in their differences, Ball and Barber are complements. For Ball, the creation of the panorama is a plot point; Barber places the work into context, claiming Muybridge only photographed cities so that they could look grand and imposing: “More mundane presences and experiences of the city habitually escaped Muybridge’s photographic attention.” Where Ball journalistically describes how Edison may have taken credit for Muybridge’s ideas, Barber muses on the meaning of derelict movie houses, one of many seemingly random digressions prompted by musings on Muybridge’s legacy. And Barber’s combing of Muybridge’s scrapbook is a gratifying resolution to Ball’s description of the photographer’s failure to be taken seriously even on a superficial level late in his life.

Images from Edward Muybridge

While Barber has chosen to bring Muybridge into the present day through semiotics, Ball uses the techniques of popular nonfiction, and this can be to the book’s detriment. The Inventor and the Tycoon leans on the true-crime convention whereby the crime must reveal some greater characteristic about the criminal. Ball describes the murder of Harry Larkyns, for instance, as “precise and ecstatic, and therefore a shooting suited to the shooter.” Some eighteen pages later, Ball describes Muybridge’s precarious perch on a precipice in a self-portrait as “unmistakable ecstasy,” and later compares the art and the murder, both “ecstatic moment[s].” The murder-as-art motif begins to seem repetitious—a clichéd assessment of artistic temperament.

But if the crime itself is fairly straightforward, Muybridge’s life and milieu are intriguingly intricate. Where Ball, a member of the Yale faculty, excels is in creating the historical panorama, framing both Muybridge and Stanford as players in an unsettled, volatile landscape. California in the last decades of the nineteenth century was obsessed with goings-on out East but tied to its industrious, earthy beginnings. The conflicted interests and a sense of competition with the East gave rise to a deep interest in innovation both scientific and social—a dynamic that that allowed a true eccentric like Muybridge to rise to fame.

The allure and the distinctiveness of the West resounds clearly in Robert J. Seidman’s Moments Captured, a deeply strange romance novel that posits that Muybridge killed the lover of his girlfriend, a feminist and dancer, rather than that of his wife. In this version of the Muybridge murder trial, Muybridge, who in real life admitted the murder he committed was premeditated, gets reinvented as a romantic, announcing of his beloved: “She’s got more character than all of San Francisco.” Both Muybridge and his fictional lover, Holly Hughes, have headed out West to clarify their respective, pioneering arts. “Like your photographs, Mr. Muybridge,” she tells him when they first meet “my style of dance is new in America.”

Edward Muybridge photographed by Carleton Watkins

Through such exchanges and through its brazenly counterfactual nature, Moments Captured confounds the reader vaguely familiar with Muybridge’s life. The reader entirely unaware of Muybridge must wonder why exactly his reputation has survived. Though Muybridge is the author’s explicit hero, Seidman treats him much more cruelly at times than either other author, portraying him as Edison’s hanger-on toward the novel’s end. This makes him a more sympathetic romantic hero, but it does little to justify having just read three hundred saccharine pages on the man.

Moments Captured functions best as an exhibit of how we really speak about our legends: a bathetic spin on every setback, with the truly evil stuff replaced by an out-and-out lie. For Seidman, Edward Muybridge is Steve Jobs, a brilliant innovator whose lesser moments are rationalized away. Though the book is bizarre to the point of near unreadability, it is a wonderful tribute: Muybridge is a hero of a Californian dream, his every misstep, in Seidman’s telling, inspired by love.

But a still greater tribute to his influence is the simple fact that three contemporary writers have presented three utterly disparate visions of the man. Dead for 108 years, Muybridge is still in motion—a subject of study whose mutability is the very point.

Daniel D’Addario is the culture reporter for Salon. He has also written for The New York Observer, Slate, and Out. Follow: @DPD_