[In his article, The Creed of an Aesthete (in our issue of January 25th), Mr. Clive Bell said: “Mr. Bernard Shaw ... is not an artist, much less an aesthete ... he is a didactic.” He referred to Mr. Shaw’s rejection of the Darwinian theory because, by depriving Beauty, Intelligence, Honor of their divine origin and purpose, this theory deprives them of their value. To Mr. Bell’s mind, Mr. Shaw feels that “if Life be a mere purposeless accident, the finest things in it must appear to everyone worthless.” The sooner Mr. Shaw knows that this is not so, the better, says Mr. Bell, and proceeds to explain his own creed: “always life will be worth living by those who find in it things which make them feel to the limit of their capacity.” “The advantage of being an aesthete,” he declares, “is that one is able to appreciate the significance of all that comes to one through the senses: one feels things as ends instead of worrying about them as means. ... Whatever is precious and beautiful in life is precious and beautiful irrespective of beginning and end.”]

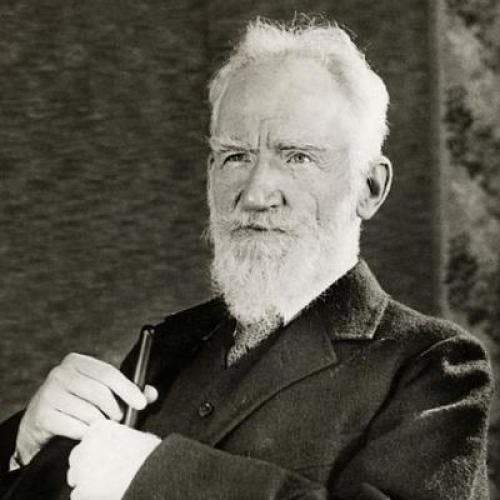

As will be seen in the above article, my friend Clive Bell is a fathead and a voluptuary. This a very comfortable sort of person to be, and very friendly and easy and pleasant to talk to. Bell is a brainy man out of training. So much the better for his friends; for men in training are irritable, dangerous, and apt to hit harder than they know. No fear of that from Clive. The layer of fat on his brain makes him incapable of following up his own meaning; but it makes him good company.

A man out of condition muscularly not only dislikes rowing or boxing, but cannot conceive anyone liking them. A man out of condition mentally not only dislikes hard thinking, but cannot conceive anyone enjoying it. To Falstaff, Carpentier is an object of pity. To Clive, Einstein is the most miserable of mortals. So am I.

He is mistaken as to both of us. Intellect is a passion; and its activity and satisfaction, which can be maintained from seven years old to 107 if you can manage to live so long, are keenly pleasurable if the brain is strong enough for the exercise. Descartes must have got far more pleasure out of life than Casanova. Hamlet had more fun than Des Grieux, who tried to live on his love for Manon Lescaut, relieved by cheating at cards. Clive tells us how he poisons the clear night air of London with his cheroots after an evening of wine, woman and song; and he is contemptuously certain that he has enjoyed himself far more than a handful of old gentlemen in a society of chemists, mathematicians, biologists or what not, discussing the latest thing in quantums of energy, or electrons, or hormones. It is the interest of the tobacconist, the restaurateur, the theatrical manager, the wine merchant and distiller, to suggest that delusion to him. And what a silly delusion it is! No pleasure of the first order is compatible with tobacco and alcohol, which are useful only for killing time and drowning care. For real pleasure men keep their senses and wits clear: they do not deliberately dull and muddle themselves. I have not the smallest doubt that when the human mind is as fully developed as the human reproductive processes now are, men will, like the ancients in Back to Methuselah, experience a sustained ecstacy of thought that will make our sexual ecstacies seem child’s play.

Clive is troubled—you know it when he cries Who cares?—because a rose grows out of manure. This comes of taking hold of things by the wrong end. Why not rejoice because manure grows into a rose? The most valuable lesson in Back to Methuselah is that things are conditioned not by their origins but by their ends. What makes the Ancient wise is not the life he has lived and done with but the life that is before him. Clive says why not live in the present? Because we don’t, and won’t, and can’t. Because there is no such thing as the present: there is only the gate that we are always reaching and never passing through: the gate that leads from the past into the future. Clive, meaning to insist on static sensation, slips inevitably into talking of “the significance of all that comes to one through the senses.” What then becomes of his figment of sense without significance? “Whatever is precious and beautiful in life,” he says, “is precious and beautiful irrespective of beginning and end.” Bosh! The only sensations intense enough to be called precious or beautiful are the sensations of irresistible movement to an all-important end: the only perceptions that deserve such epithets are perceptions of some artistic expression of such sensation or pre-figured ideal of its possibilities. The pain with which a child cuts its teeth, though felt, is not suffered because the child feels it as Clive pretends to feel his pleasures: that is, it cannot anticipate the next moment of it nor remember the last; and so, fretful as it may seem, it does not suffer at all. If Clive ever gets his pleasures down to the point at which he also does not anticipate the future or remember the past, he will not enjoy it in the least. In short, his imaginary present and its all sufficing delight is unconsidered tosh.

The reason Clive enjoys his suppers is that he first works hard enough to need relaxation—at least I presume and hope he does. If he did not he would be miserable, and would probably have to take to drugs to enable him tobear his pleasant evenings at the Russian Ballet. Even now he cannot get through them without the aid of cheroots. I never eat supper; I never smoke; I drink water; and I can sit out Petrouchka and enjoy the starlight in Piccadilly all the same. But clearly, if I could be persuaded that Petrouchka, instead of being a relaxation, is as creative as the Piccadilly starlight is recreative, I should enjoy it a thousand times more. So would anybody.

No, my Clive: in vain do you sing

Sun, stand thou still upon Gibeon,

And thou, Moon, in the valley of Ajalon.

They will not stop for you. Lopokova will dance, as you say; but when you stretch your arms to her and cry

Verweile doch, du bist so schön

you cannot stop, either of you, any more than Paolo and Francesca could stop in the whirlwind. You delight in the music of Mozart; but does it ever stop? It ends; but your delight ends with it. You are a destinate creature, and must hurry along helter skelter; so what is the use of waving your cheroots at us and assuring us that you are motionless and meaningless? There is nothing in the world more ridiculous than a man running at full speed, and shouting to everyone that he is in no hurry, and does not care two straws where he is going to.