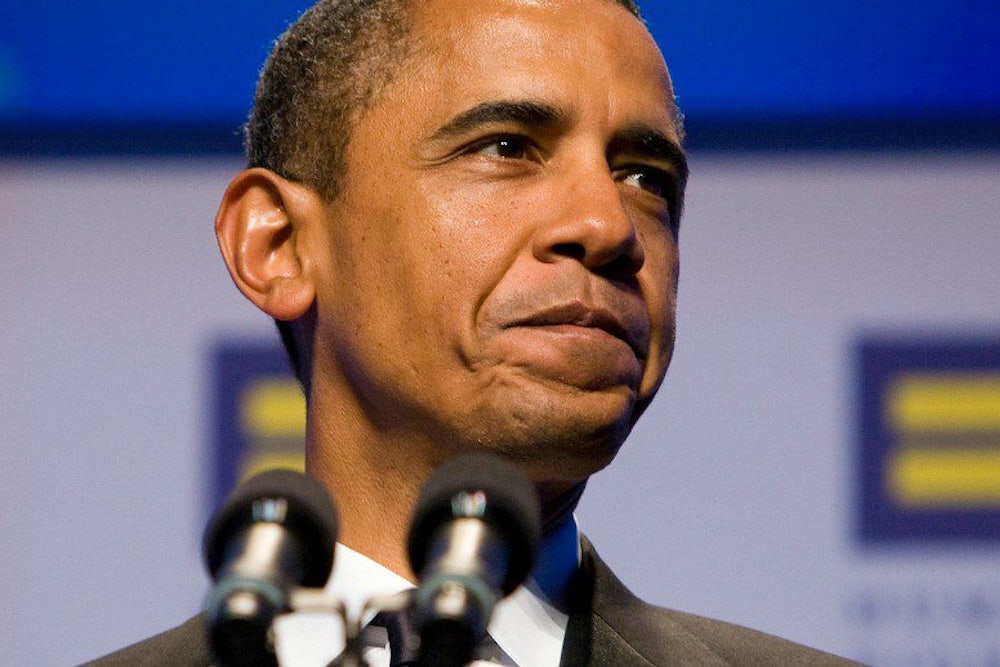

President Obama’s announcement that he supports same-sex marriage may have had an immediate impact on political discourse, but the same can’t be said of its implications for constitutional jurisprudence. For those hoping for a forthright defense of constitutional protections for gay rights, Obama’s announcement seemed to raise more questions than it settled.

Commentators were right to point out that Obama’s announced position—that he supports gay marriage, but every state should decide on the matter for itself—is inconsistent with the position his administration took last year in opposing the Defense of Marriage Act. Indeed, the Department of Justice announced that “strict scrutiny” of anti-marriage laws reveals them to be motivated by anti-gay animus, and thus unconstitutional; in other words, Attorney General Eric Holder suggested this was precisely an issue that states aren’t free to decide on their own.

In contrast with such bold declarations of principle, Obama famously cited the personal nature of his “evolution:” It was motivated, he said, by conversations he had with wife and his daughters about friends who have gay parents. But it would be hasty, not to mention cynical, to conclude that Obama invoked his family to avoid having to discuss constitutional protections for same-sex marriage. Rather, those invocations may have been a shrewd suggestion of how such protections can best be achieved.

PSYCHOLOGICAL RESEARCH HAS shown that the reasons Obama cited as having changed his mind—in particular, conversations with his wife and daughters about their gay friends—is precisely what has persuaded a bare majority of Americans to embrace gay marriage in recent years. According to Gregory Herek, a psychologist at the University of California at Davis who is a leading authority on how people change their minds on matters involving gay and lesbian discrimination, Obama’s personal evolution was entirely typical. Simply having a lesbian or gay friend isn’t enough to change people’s minds, Herek says. Instead, the decisive factor is whether someone has had a personal conversation about what it’s like to be gay and how it influences a person’s life.

In a 2005 study, however, Herek found that a significant majority of gay men and lesbians hadn’t had those kinds of conversations with straight people in the past year, even though they were out of the closet. This is where wives and daughters come in. Herek argues that in the last several years public opinion has been transformed by heterosexual women like Michele Obama taking the role of “ally” for gays and lesbians—initiating conversations with their male relatives about marriage equality, and communicating the idea that they won’t tolerate prejudice.

“One of the things we see in the research consistently is that heterosexual women are pretty far ahead of heterosexual men on this issue,” Herek told me. Evan Wolfson, executive director of the group Freedom to Marry, agrees. “We used to say knowing someone who was gay is the biggest factor in leading people to change their minds,” he says. “But buried in that data was something more specific: Best is having conversations with people who are gay, and second best is having conversations with non-gay people who care—those conversations and engagement are what help people resolve their conflicts or concerns.” Herek’s research suggests that, over the next few years, so many straight American men will have such conversations with their wives, daughters, and gay acquaintances that a new social consensus will develop in favor of gay marriage.

The constitutional significance of this should be clear. The emergence of a consensus on gay marriage could spare the country contentious legalistic arguments about levels of constitutional scrutiny, of the sort that the Department of Justice has thus far offered about DOMA. Once the moral case for marriage equality has moved from being a contested to an uncontested social principle, courts will be able to—indeed, they will be expected to—extend the right to marry to gays and lesbians under even the most relaxed constitutional review. In the 2003 Lawrence case, the Supreme Court said that anti-gay animus can never justify a law that discriminates against gays and lesbians—and if the vast majority of the country no longer sees gay marriage bans as a legitimate commitment to preserving tradition, animus will be the only plausible motivation to discern in them. Just as the Supreme Court, by 1967, was able to say that “everyone knows” that opposition to interracial marriage was based on animus against African American inferiority, so might the Court soon be able to say that “everyone knows” that opposition to gay marriage is based on unconstitutional animus against gays and lesbians.

Of course, it is one of the greatest challenges of constitutional law to identify the point at which a society’s belief in a particular conception of equality has moved from a contested principle to an uncontested one. Traditionally, courts have counted up the number of states that recognize a right in an effort to discern a national consensus—and by that standard, gay marriage hasn’t cleared the hurdle, since 38 states have laws or constitutional provision limiting marriage to relationships between men and women. But the courts may soon be in the position to determine that state laws have lagged behind the transformation of the public’s understanding. That depends, though, on more Americans mirroring Obama’s process of “evolution” on the issue. And if Herek’s research is correct, they almost certainly will.