The Confines of Criticism

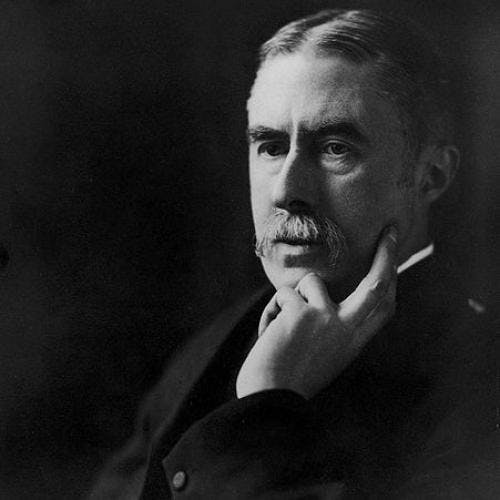

by A. E. Housman

(Cambridge University Press; $2.95)

Eight and fifty years ago A. E. Housman delivered at Cambridge a lecture conceived in bitterness at what was happening to scholarship. He singled out an Oxford man, Algernon Swinburne, for special blame. Swinburne had taken as a masterpiece one line by Shelley that Housman wanted to demonstrate was unfinished (Housman couldn’t demonstrate Shelley’s dissatisfaction with it for sure; hence the publishing delay of eight and fifty). The line—“Fresh spring, and summer, and winter hoar”—wasn’t important, but the Swinburne procedure with it was. Swinburne had abandoned observation for epithet. He had said that “the melodious effect of [the line’s] exquisite inequality . . . was a thing to thrill the veins and draw tears to the eyes of all men.” If he had played scholar, Housman felt, rather than violinist he might have noted that the line was short a foot and a season—and let readers judge for themselves its exquisiteness.

The year (1911) of Housman’s lecture was also the year of the publication of the eleventh edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, a great year, maybe the last great year of a dying cause. In 1912 came Poetry of Chicago, followed closely by Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, the War and all those other persons and things we now think of nostalgically as modern. Housman was not modern; he was a crusty old Latinist who concluded his lecture with a spirited diatribe against keeping up with the Joneses, what he called “servility shown toward the living.” The servility was often found “in company with lack of veneration for the dead.” Housman counseled thinking “more of the dead than of the living.” He added:

The dead have at any rate endured a test to which the living have not yet been subjected. If a man, fifty or a hundred years after his death, is still remembered and accounted a great man, there is a presumption in his favor which no living man can claim; and experience has taught me that it is no mere presumption. It is the dead and not the living who have most advanced our learning and science; and though their knowledge may have been superseded, there is no supersession of reason and intelligence. . . . If our conception of scholarship and our methods of procedure are at variance with theirs, it is not indeed a certainty or a necessity that we are wrong, but a good working hypothesis.

The Cambridge Press must have felt very daring in resurrecting these now treasonous words. Yet Pound, though he hated Housman and was in his time the noisiest advocate in Europe of making it new, would not have denied the past its due. And he would have been delighted at the attack on Swinburne. Similarly, most modern students of literature would until recently have gone along with Housman’s major premises, though perhaps thinking Housman himself an old fuddy-duddy. The past was, literally, depended on, until recently, by all camps; and by most the extravagances of Swinburne’s showbiz criticism were deplored.

When I was in college the Swinburne sort of thing was well represented by Professor Billy Phelps at Yale. At that time both the old scholars and the New Critic, though at each other’s throats, could agree to deplore Billy. Billy was a great popularizer, a legislator of low-brow tastes, an addict like Swinburne of purple appreciations. Billy perfectly satisfied his readers’ and listeners’ demands by doing for them what Housman in 1911 most scorned, presenting them with rusty conventional opinions “sprinkled over with epithets like delicate, sympathetic and vital.” Looking back I realize now that nearly the whole of my literary education—in works ancient or modern—was designed to combat what Billy encouraged. Particularly he encourage the vice I. A. Richards, another Cambridge man, inveighed against: the stock response. From the old Latinists through the exponents of making it new the great sin against literature in those days was not to read it with one’s own eyes and mind but to judge it according to opinions gratuitously purveyed by the likes of Billy.

Housman and the old scholars believed independence from faddish current opinion could be achieved by respecting both ancient texts and ancient authority. The New Critics favored the authority of the texts alone, ancient or modern. The difference was sometimes construed as that between the inductive and deductive mode, and it was certainly a difference sufficient in 1940 to tear English departments apart. Yet Billy and his kind remained, for both parties, a greater threat than destruction. When he retired at Yale in 1940 most members of the literature faculty were overjoyed; they felt that education could now resume.

Now another thirty years have passed, of which ten have been the Terrible Sixties. The sixties discredited evenhandedly the old scholars and the New Critics, leaving English departments on the ropes and increasingly dependent for their clientele upon offerings of that non-course known as Creative Writing (imagine Housman’s lecture on Creative Writing). The sixties also reintroduced Swinburne and Billy with a vengeance, in the form of what Susan Sontag, who is not to be blamed for the whole thing, called an erotics of criticism. If the Howling Seventies give us more of the same, literary people of my generation and older will die even sourer than Housman.

A modest reversal is not more likely but pleasanter to contemplate: a thermidorian reaction. Some semblance of the past’s authority would be restored, and the mind’s role in creation and criticism reacknowledged. Suddenly students would discover quaint old characters like Housman, and loftily tell their parents about them. Eventually Look might publish a spread about Housman, together with wild bearded poets busily counting their feet.

Perhaps the Cambridge Press had the same crazy dream before they issued this book. In any event, here, in a mere fifty pages, is a past so remote as to be attractive, and an academic position so stodgy it’s radical. Read Housman; he’s the most.

This article appeared in the November 29, 1969 issue of the magazine.