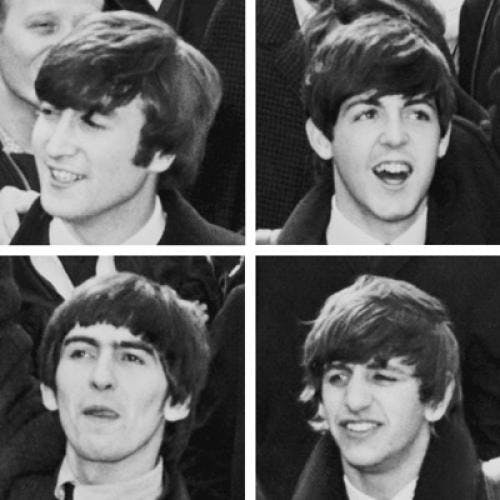

The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics,

edited by Alan Aldridge

(Delacorte Press, 5.95)

"I was the kingpin of my age group," said John. "The sort of gang I led went in for things like shoplifting and pulling girls' knickers down."

"We had masters who just hit you with rulers, or told us a lot of shit about their holiday in Wales or what they did in the Army," said Paul. "Never once did anyone make it clear to me what I was being educated for."

George had school complaints too: "Some schizophrenic jerk just out of training school would just read out notes to you which you were expected to take down. . . . Useless, the lot of them. . . . They were trying to turn everybody into rows of little toffees."

Unlike the others poor Ringo didn't have a chance to rebel as a child, and he didn't have "the education to do anything clever" because he was sick all the time. He stole a few things from Woolworth's ("just silly plastic things") but he was a late bloomer and the last Beatle to join up. He felt out of things for a while but made the scene finally so that he received equal time in the authorized biography of the Beatles by Hunter Davies {1968).

The quotations above are from the biography, maybe the first authorized biography deliberately devised to make its subject(s) look bad. The sixties were needed before the full monetary rewards of promoting dropouts and dropoutness could be realized. The Beatles found out early where the new big money was — it was in good anti-bourgeois vice — and with remarkable prescience they then hung close to the appropriately dissentious fads, right through LSD and the mysterious East, until they reached their present rich old age of 28 (average). For as John put it in the new book, "You see we're influenced by whatever's going."

John might have added, had he not been modest (he did say once that they were bigger than Jesus, but that was in Nashville), that they were not only influenced but influences. One of my children was just four when the first Ed Sullivan Beatle program occurred, and the "yeah yeah yeah" in a stirring love song released him instantly from whatever small influence we had had upon him. His head began to bob, he stamped his feet, he went off to find a drum - and grow hair. He has never recovered.

The new book, containing most of the lyrics the Beatles have themselves written, is another instance of their clever tactics. The lyrics are not bad, but they would have looked naked and skinny by themselves, not revolutionary. Most of the Beatles' message of dissent, and most of the profit has been in their music, not their words. The problem of the book was to find something to accompany a lyric on a page, something equivalent to Beatle noise — a problem handsomely solved with pictures, hundreds of wild, sexy, psychedelic, noisy pictures.

Half the new artists of the now world were harnessed to the job, and the result is extremely now. The editor, Alan Aldridge, is himself a clever young now dropout with appropriately long hair, and he describes his occupation with a phrase that covers the book itself: graphic entertainment. In graphic entertainment as in music the Beatles obviously let whatever's going influence them, but as with music they will doubtless in turn encourage more of the same. The book, priced low for so much genuine nekkid art, will sell like hotcakes and breed dozens of publishing imitations, some perhaps even using Dante, or Shakespeare's sonnets. (Think! The Dark Lady! I shouldn't have mentioned it.)

What is impressive about the lyric entertainment in the book is how simple and sentimental and corny most of it is without the accompanying dissonance. Those who take deep soundings into the meanings of Beatle words should pay more attention instead to the meaning of musical bronx cheers — which are where the big Beatle profundity lies. A few lyrics have innuendoes about drugs and sex, and a few are openly porn, notably "Why don't we do it in the road"; but mostly they are straightforward love songs out of the twenties. Tin Pan Alley had its innuendoes too, but people just laughed at them. Now in our age of revolution we are asked, by editor Aldridge among others, to revel in ambiguities and hidden meanings. The revel is simply not there; it is in a bright and mildly tricky verbal surface enforced by, of all things, rhyme and rhythm:

Michelle ma belle

Those are words that go together well.

And:

It feels so right now, hold me tight.

Tell me I'm the only one.

And then I might

Never be the lonely one.

Those are deep like Irving Berlin. Ah, but Aldridge would have me look in the deep songs such as those in the Sgt. Pepper album, where there are deepnesses about going on trips and even a bit of Liverpool phallic. Yes, and there is surrealism too, as in lines like "keeping her face in a jar by the door" (stupidly I thought that described a woman and her make-up). I have looked at these now, and I still think the lyrics are simple (I refuse to play them backwards). What impresses me is that the Beatles themselves keep saying they are simple. Their very first song, composed by John and Paul together, remains the model for at least a third of the poems. It begins, undeeply but pleasantly, with a clever little syntactical arrangement, its only distinguishing feature aside from the fourth line's "who-ho":

Love, love me do.

You know I love you.

I'll always be true

so please love me do, who ho

love me do.

Another third of the poems is like the first third except that a good deal more is made of the "who ho" motif. I mean that this second third clearly deviates from the simple Romantic Love they began with, by jazzing the romance up. Nothing unusual here. Tin Pan Alley moved readily from elementary corn to corny wit like, "Strictly between us/ You're cuter than Venus/ And what's more you've got arms." Beatle wit, in the jazz tradition, is more forcefully a part of the music and the performance than the words; it's in the head wagging and the gestures and the klaxon like sounds where there should be sweet violins - an early model would be Fats Domino singing "Blueberry Hill." Yet with the Beatles the dissonance will clearly be present on the page, as not in "Blueberry Hill." The following sour lyric, for example, would seem to be a sort of parody of romantic songs in which the girl is going away and the boy is heartbroken:

Do what you want to do.

And go where you're going to,

think for yourself, 'cos

I won't be there with you.

In songs like this the Beatles are in effect playing dropout from jukebox Romantic Love. They are playing tough with it. They are little boys throwing snowballs at a stovepipe hat. And yet they constantly pay their respects to it by keeping the "I love you's" and the simple rhymes and rhythms as a base.

The third third is of course the deep third, containing numbers with exotic imagery from the land of the lotus eaters, and a few ironic monologues or dialogues in which they play the parts of unpleasant bourgeois people ("Revolution," "Try To See It My Way," and "She's Leaving Home"). These songs are more than tricky. I respect them. Perhaps I cheat them by underplaying them and emphasizing the other two thirds of the Beatle repertoire. The Beatles, I feel, can afford to be cheated. Anyway it was the deep-rooted conventionality of the first two-thirds of the selection that most impressed me. I was oddly taken back in my own mind, as I read these lyrics, to the old Orson Welles movie Citizen Kane, in which the mystery of the rich old man's last death-bed word, "Rosebud," as well as the mystery of what had made him tick all his life, is laboriously sustained to the very dramatic end when the flames of Kane's great house burning finally consume a small sled up in the attic. On the sled is the word "Rosebud."

Tin Pan Alley is the Beatles' rosebud, and a convincing rosebud it is for four young capitalists selling 225 million records and saving the British pound. But what should be the rosebud for four of the world's leading dissenters? Neither honest art nor thoroughgoing dissent has ever accommodated itself well to money and middle-class opportunism. The Beatles have ringed their art with layer upon layer of dissonance, but in the still heart of the lyrics the deep truth is revealed. Hell of a way to run a revolution.

This article appeared in the November 7, 1969 issue of the magazine.